Snapshot: Lebanon Tightens Its Grip on Syrian Refugees

In Lebanon, Syrian refugees face deportations, vigilante violence, and soaring incitement.

Four years after Yahyia fled Syria for Lebanon, what he hopes for isn’t too much to ask. He just wants to live somewhere where he can get legal residency papers and stable work, somewhere without a war. He would go anywhere—whether elsewhere in the Middle East or Europe. Or as he puts it: “Anywhere but Lebanon or Syria.” But as long as he remains in Beirut, he won’t even stray from Hamra, the neighborhood where he shares a cramped, one-bedroom apartment with six other Syrian refugees.

When we met at the small alleyway café where he works early one afternoon in November, the thirty-two-year-old told me how he had served in the Syrian army throughout much of the civil war that broke out in 2011. Although many communities across the map of Syria fell under the control of a slate of armed opposition groups, serving in the military wasn’t rare in his hometown of Sweida, where the mostly Druze population largely remained loyal to Syrian President Bashar al-Assad’s authoritarian government. Yahyia spoke at a rapid clip but kept his voice low, pausing only whenever pedestrians passed by. Loyal to the government or not, he couldn’t provide for his wife and daughter on the anemic salary the military paid him, especially as the cost of living in a sanctioned and war-torn country continued to spike.

When Yahyia left home in 2019, he did so with the help of smugglers. He walked for miles through the mountainous borderlands and crossed into Lebanon, a dangerous journey that some 20,000 displaced Syrians made between January and early September of this year alone. Since coming to Lebanon, Yahyia has worked under the table and lived without legal residency documents that can be difficult for Syrians to obtain. For Yahyia, a renewed clampdown on Syrian refugees means he has to be aware of which areas have security patrols, where they have set up checkpoints on any given day. “If they catch you at any checkpoint,” he said, “they could immediately deport you and hand you over to the Syrian army.”

Of the estimated 1.5 million Syrians in Lebanon, only around seventeen percent have legal residency. For those without papers, the odds of being forcibly returned to their home country have swelled. In recent months, Lebanese authorities have ramped up a clampdown on refugees, carried out mass arrests, and hauled people back to the border in extrajudicial returns.

The way Yahyia puts it, going back to Syria isn’t an option, not even for many of those who fought under Assad’s banner: once you’ve abandoned service, he explained, the government considers you just as traitorous as those who took up arms against the state. “They’ll put you in prison and forget you there,” he said.

Imagine—airstrikes and barrel bombs level your neighborhood, turn homes, schools, and hospitals into mounds of debris. Many of your neighbors, friends, and relatives either join the military disappearing your community or sign up with armed opposition groups, some of them hardline. You sell what you can, pay smugglers to get you across a border, and try to build what you can of a life in a new country. Some people you know are shot, maimed, and killed, and others drown at sea.

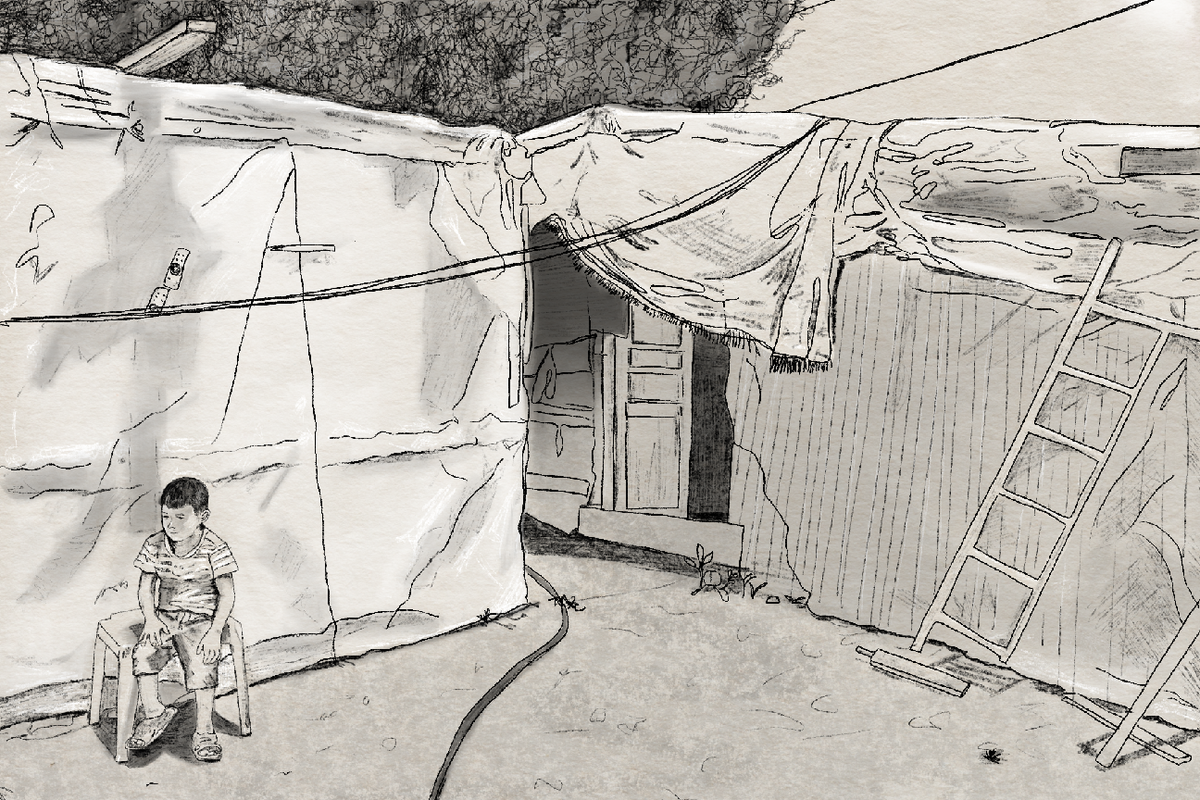

Now imagine—in the place you sought refuge, you either live in a camp bottlenecked with families and children, perhaps even in a ramshackle tent, or in a rundown apartment alongside others like you, people who came for refuge. You work rough jobs, often at the risk of exploitation. You face the risk of being attacked by people who don’t want you in that new country. You know answering a knock at the door could end with you handcuffed and dragged back to the very country from which you fled for your life.

Since 2011, what started as a popular uprising against an authoritarian government turned into a full-scale civil war that tore Syria apart at the seams. Although fighting has eased, the war has displaced more than half of the country’s prewar population of more than twenty-three million. The U.S., Turkey, and Gulf countries, among others, backed various opposition groups. Russia, Iran, and the Lebanese armed group Hezbollah fought in the service of the Assad government. In early 2014, less than three years into the war, not long after the death toll topped 100,000, the United Nations stopped keeping tally—the bodies had stacked up too high and too quickly, the fighting had grown too fierce, to continue to accurately confirm the number of deaths. Twelves years since the first protest, the U.N. refugee agency, known as UNHCR, estimates that the war has internally displaced more than 6.8 million Syrians. Millions more pushed onward to neighboring countries or made the grueling trek to Europe.

Even outside of Syria, the misery hardly eases. On the European Union’s external borders, Syrians and other refugees and migrants often face threats, beatings, and extrajudicial expulsions known as pushbacks. Others have boarded unreliable boats to cross the Mediterranean Sea, sometimes drowning when the vessels capsize. In Lebanon and Turkey, for instance, authorities can stop them on the streets or kick down their doors, whisking them off to detention centers or throwing them into the deportation machine—a process that effectively ends with a death sentence for some.

Between January and August, Turkey deported more than 29,000 Syrians to their home country, according to the rights group Syrians for Truth and Justice. Jordan has deported thousands, and its government has spoken of plans to send yet more back. In April and May alone this year, the Lebanese army summarily deported thousands of Syrians, including unaccompanied children, according to Human Rights Watch.

In Lebanon, the wave of deportations came amid a campaign of intense incitement against Syrians. Since Lebanon’s economic crash started in 2019—its currency collapsed, inflation soared, and residents have suffered shortages of necessities like water and electricity—politicians have increasingly sought to offload the blame on refugees in the country.

In June, former president Michel Aoun complained of “the dangerous position of Europe, which refuses to repatriate refugees, tries to integrate them into Lebanese society, and uses every means possible to prevent their return under the pretext of protecting them.” Three months later, caretaker Prime Minister Najib Mikati told a cabinet meeting that the presence of Syrian refugees “threatens our entity’s independence and could create harsh imbalances that could affect Lebanon’s demographic.”

But incitement has other consequences—including vigilante violence. Anti-Syrian sentiment isn’t new in Lebanon, parts of which the Syrian military occupied for nearly three decades, but the economic catastrophe has further fueled xenophobia, UNHCR said in July 2022. At the time, as politicians ramped up calls to forcibly deport Syrians, local authorities in some parts of the country placed refugees under curfews. Elsewhere, bakeries were asked to sell to Lebanese residents before they sold to Syrians. In many cases, locals attacked Syrians, using sticks or guns. “There were incidents across country of people beating up Syrian refugees, people setting fire to their homes, [and] people evicting them from their homes,” said Aya Majzoub, Amnesty International’s deputy director for the Middle East and North Africa.

In May, Amnesty International, along with other Lebanese and international rights groups, called on Lebanon to abandon summary deportations, explaining that some refugees who had been handed over to Syrian authorities later disappeared or ended up behind bars. “We and other human rights organizations have consistently documented that refugees deported back to Syria are not safe,” Majzoub added. “There have been arrests, torture, forced disappearances, killings, and sexual violence.”

When Amnesty International put out statements calling for an end to such deportations, Majzoub said, the rights group received a slate of angry messages, accusations of being traitors, and death threats. “The backlash we got was really something I’ve never seen before on any of our work,” she recalled. “It was quite alarming at the time.”

When I met Hakim, a twenty-three-year-old from Aleppo, standing on a sidewalk near Hamra Street, he said he hadn’t had negative exchanges with his Lebanese hosts. Still, he admitted that he felt the social environment turning even more against Syrian refugees. He came to Lebanon legally six years ago, but over time, his residency documents lapsed. Last month, after hearing stories of authorities detaining other Syrians at checkpoints, he started the arduous process of trying to renew his residency permit. It wasn’t that he didn’t want to go back to Syria—he wants to visit his mother, who has fallen ill since he left—but he had slipped out of the country to dodge his mandatory military service. He feared what deportation would lead to: losing his freedom or worse.

Adding to his unease, he said, is the knowledge that he could fall in the crosshairs of vigilante violence. In early October, an argument over a car accident led to a fight between local Lebanese residents and Syrian factory workers in Beirut’s Doura neighborhood. As tensions spiked, hundreds of locals reportedly surrounded the factory and tried to break down the door. Several people were injured before Lebanese security forces showed up. The dispute came a day after caretaker Interior Minister Bassam Mawlawi called for a “crackdown” on Syrians. For several days after that incident, Hakim didn’t return to his neighborhood, the mostly Christian area of Ashrafieh, because he worried more violence might follow. “It’s frightening,” Hakim said, “and of course, it’s not just.”

That same day, I met Mustafa, a thirty-two-year-old construction site boss from northeastern Syria’s al-Hasakah, at a coffee shop in Beirut. Like Hakim and Yahyia, he made the decision to leave when the military summoned him to carry out his mandatory service. He told me that although he has legal residency documents and mostly kept the company of Lebanese friends, he knew most Syrians felt more fearful nowadays. He spoke over the clatter of a construction crew across the street, and a Lebanese woman sitting nearby listened in on our conversation. “If there’s one Syrian who does something wrong,” he said, “some people will treat all Syrians differently.”

As he talked, the woman leaned forward, shook her head, and then interrupted. She didn’t want to say Mustafa was wrong, she insisted, but she wanted me to know that not all Lebanese people harbored xenophobic sentiments against Syrians—despite the fact that Mustafa had said nearly the exact same thing only moments earlier. She had also visited Syria, and she thought it was important to point out that “there is also racism” there. Unlike with Mustafa’s life in Lebanon, the woman hadn’t gone to Syria as a refugee and ended up marooned by war, unable to return home.

Back at the alleyway café in Hamra, Yahyia said he planned to keep his head down and continue searching for a way out of Lebanon. What other choice did he have? Every day he spent in Beirut was another day he risked being snatched up and sent back to Syria. “There’s a lot of fear,” he said. “When you deliver someone to the Syrian government, you’re handing them over to death.”