In-conversation: Anna Lekas Miller on Love in a Bordered World

Anna Lekas Miller discusses relationships and love in a world divided by borders.

In her new book, journalist Anna Lekas Miller tackles a broad subject: how borders and a system of movement based on passports take a toll on love and relationships.

Published in June, Love Across Borders: Passports, Papers, and Romance in a Divided World is Lekas Miller’s first book. It’s a deftly woven blend of reportage and memoir in which she reports on relationships divided by borders the globe over as well as her own relationship.

The book alternates between these reported vignettes and her own story with Salem, the Syrian journalist who eventually became her husband, and their struggle to find a place they could call home together.

Lekas Miller’s reportage, often on migration and borders, has appeared at New Lines Magazine, The Intercept, and Hyphen, among others.

Lekas Miller spoke with Long Road Magazine’s Farhinisa Campana about the history of passports, the legacy of colonialism on freedom of movement, and what a borderless world might look like.

Fahrinisa Campana: Since you are a journalist and writer, could you start with speaking a little bit about your work in general and what you’ve been focusing on lately?

Anna Lekas Miller: Oh, that's a big question, and I love that you said both a journalist and a writer. I do think that although there is a distinction there, and that distinction is very much seen in Love Across Borders, it was a space where I was both doing a lot of journalism when I was gathering the stories that are in Love Across Borders, but then I was also very much baring my soul and writing my own story, which definitely does not have the unbiased sort of distance of being a “journalist.” So, I feel like I've been moving more towards being a writer with writing about those types of things.

But if we're talking holistically, I got my start writing from a young age. One of the first places I was based was the West Bank and occupied Palestine. I was reporting on the lives of Palestinians living under Israeli occupation, and it was really from then that I was first struck by this idea of how curtailed some people's freedom of movement is when compared with others’. It was very much from my perspective, as an Arab-American journalist myself, where even though I shared a culture with so many people that I was talking to day to day, I had a U.S. passport and could travel and pick where I reported and pick the stories that I chose to cover. In a way, that was the definition of freedom, the definition of privilege in so many ways. This continued as I was reporting in the Middle East, a place I'm so connected to personally, but then felt like I had this huge difference with an American passport.

That's very much what carried me into eventually writing Love Across Borders, because I fell in love with my now husband, who is a Syrian journalist. We had everything in common and very much fell in love over how much we wanted to both see and experience the world and travel and tell stories. Yet, I had a U.S. passport, and he had a Syrian passport. He eventually got kicked out of Turkey, which is the country we were both living in at the time. That moment was both the catalyst for my own story of Love Across Borders, but also the idea for the book. Because it kind of gave me comfort, at that time. It was like, “Well, I can't be the only one in this situation.” How is love affected by this kind of inequality? How is romance affected by things like the refugee crisis, things like borders popping up, people being separated for months at a time? I set out to investigate that while I was reporting and living my own story, but that's what became Love Across Borders. That’s been the heart and soul of so much of my work, and now my work really rests at sort of the intersection of thinking about what freedom of movement really means and thinking about it in the context of love, intimacy, and emotionality.

FC: Why did you decide to broaden your search for other people who are experiencing the same thing? Beyond making the book more holistic, was it also perhaps a personal journey of yours to seek out others who were experiencing the same or something very similar?

ALM: It was a personal journey of mine, and it was also this knowledge that I did have a U.S. passport. And yes, I was able to follow Salem, my partner, to Iraq when he was deported there. Of course, it felt like this grand romantic gesture, but it was this grand romantic gesture that was facilitated by the fact that I could easily travel there.

What kept sitting with me was: What about people that can’t do that? What if we were both Syrian? What if my family had never immigrated from Lebanon and I'd grown up Lebanese, but fell in love with the same person? How would this look then? So, I was trying to tell my own story, and just be as honest and transparent about that as possible. But also, I wanted to really investigate what happens when someone does not have this privilege. And how are those people just absolutely shattered by the system even more?

FC: Let's talk a little bit about passports. You discuss in the book that passports are a relatively new institution. So, how did we end up depending on a little book called passport?

ALM: This history goes back in some ways. Because the passport, or at least a form of identification document, has been something that's been around since antiquity. You had it with the Romans. My personal favorite example that I learned about is that West African tribes used to have passport masks they used to identify themselves and see if they could trade [and] if they were friends or foes. I just love that idea of kind of this ornate mask being the identity document, as opposed to what we have today.

But then it was first really during the French Revolution that passports started being something that policed freedom of movement, though it wasn't about nationality. At that point, it was very much about the uncentered regime, kind of trying to keep the “riffraff” out of the cities. So, it was very much based on class, and based on this class system that [meant] “these people shouldn't be allowed to come to this place.”

Over time, that started evolving. You start seeing more people immigrating to North America, the United States, and a desire for controlling the types of people who could come once again popping up, very similar to the way that it was during the French Revolution. So first, it was things like, “Oh, we have to test if someone is literate,” “We have to test that they don't have mental disabilities,” “We have to test that they're not a sex worker,” or anything like that.

But then the first example where they really banned a whole group based on nationality was the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882. So that was sort of like this guinea pig—it was like, “Oh, we noticed that Chinese immigrants in particular are starting to be very successful, particularly working on the railroad.” People in the U.S. government were not pleased with that, because they wanted this country to have a white Anglo Saxon Protestant majority. So that was sort of this test that then eventually became the 1924 Immigration Act, which excluded so many people … basically anyone that wasn't from Western Europe.

That coincided with World War One, when passports started being used for national security. But that was seen as a temporary wartime measure. Then after the war, there was actually a meeting that I just think is a crazy and kind of magical moment to imagine. They were really talking like, “Okay, so are we ready to get rid of passports? Can we do this? We want to have freedom of movement back. We want to facilitate goods and services coming across borders. We want to facilitate relationships between people. We want to facilitate trust between nations.” So, there was this sort of moment where the tide could have really turned and, of course, it didn't: they chose to keep passports, and they only became more standardized, more regulated.

Over time, [there were] more and more implications depending on which passport you had. Now, in this moment when we do have such a restricted world depending on the passport that you hold, it is something that’s important to imagine. Yes, we've witnessed in our lifetimes these things that close and close and close [borders], and walls go up more and more and more. But what if we imagined even small ways that it could be more open, and that walls could come down?

FC: It sounds like passports have effectively become an apartheid-like system when it comes to freedom of movement. Would you say that that's accurate?

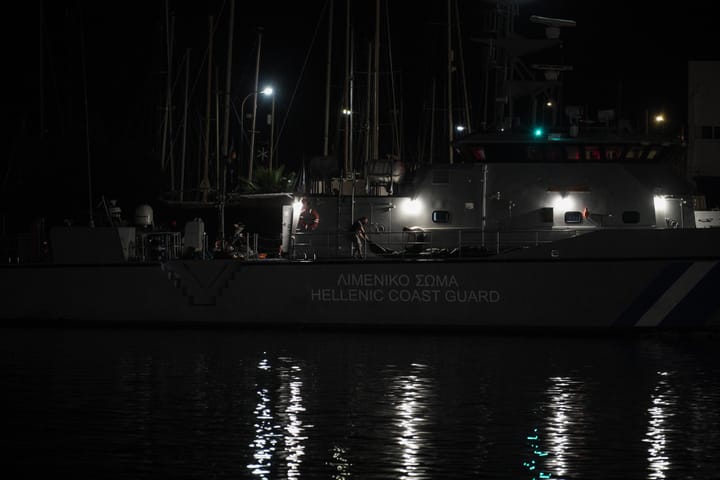

ALM: That’s a fantastic way to characterize it. But what I always say is: Just think about airports. Think about how many planes are in the sky. Think about looking at a departures board at the airport and seeing how many cities are listed and how many places that you can go. Now just imagine that you still have people boarding fishing trawlers, such as the way they did last [month] and ended up sinking in the Mediterranean, tragically. Even though we have all this technology, all these amazing ways that the world has globalized in order to facilitate trade to facilitate commerce, it does not facilitate the movement of people. It is very much only certain people [who can move freely]—people who hold those weak passports do not get to be a part of this system. So yes, it is absolutely a system of global apartheid that's based on passports.

FC: Is there a link between the legacy of colonialism, on the one hand, and borders and passports, on the other?

ALM: This idea of who is a migrant and who is a refugee was sticking out in my mind a lot while I was working on the book, and a lot of the most interesting arguments that are made about why everyone should have the right to move revolve around thinking about where economic migrants are typically coming from: a lot of countries in Africa, a lot of countries in Southeast Asia. These are the countries that were colonized. These are the countries that were colonized by Europe. And now people are too poor to be able to sustain a life in their countries.

There is a young man that I profiled in the book, this magnificently intelligent Nigerian man named Mona. He was just like, “Yes, well, Europe came and took everything from us. So now we have no choice but to go to Europe.” That’s the simplest and yet most effective way to really say it at the end of the day. The only form of reparations for colonialism would be to have [open] migration. If you can't redistribute wealth so that people wouldn't have to leave their families behind and could just have a sustainable life in their countries, you could at least make it so that people can easily come to the place that build this wealth off their backs.

FC: Are borders becoming even more difficult and dangerous to cross nowadays?

ALM: If you think about the huge mass exodus of people coming across the Mediterranean that happened in 2015 … there were a lot of journalists covering it. Of course, it's something that's still happening. But even as a journalist who continues to be passionate about covering things like this, it's harder and harder to place those stories. It’s unfortunately seen as no longer news. But it's of public interest because it's still an injustice that's ongoing. But with so many other things going on, it then gets shoved to the margins, and that just allows more injustices to happen without accountability.

I think it's not only becoming harder but that governments are even able to get away with more and more—both in the European theater of migration and also in the Americas, such as with the end of Title 42 [in the U.S.]. In a lot of ways, it is about the end of the asylum system as we know it in the United States. So, more and more is happening, and it’s more and more overlooked.

FC: You make the case for a borderless society in the book. What would that look like?

ALM: Over the years, I've talked to many people who are actively fighting and campaigning for a world with open borders, which I find so inspiring. Of course, this is something I think needs to happen a little bit at a time. And it is something that I think a lot of people are very overwhelmed by, so I'll try to make the case for what I see as an accessible vision of a borderless society.

As a U.S. passport holder, I feel like I live in a world with relatively open borders—not completely open—but I feel like I can travel wherever I want. I just have to be able to get a plane ticket. And I do feel like if a war were to happen in my country, I could probably go somewhere to wait it out. It wouldn't be an enormous tragedy. And I wish that everyone had that amount of freedom.

One case study is the way that Ukrainians have been accepted in the European Union. The E.U. said Ukrainians can be there for three years before they have to apply for asylum. That makes a huge difference. It means people can move freely, can work, can rent an apartment. It means people can live their lives. Of course, it's still difficult, and in some ways, people are still in limbo. Of course, people have still left their home and are still living with the trauma of it being quite possibly destroyed. But at least they're not living in this restricted way that so many asylum seekers are living in in countries that restrict their right to work while they seek asylum, that will give them a very hard time to seek asylum, that will threaten to deport them, that will actually deport them.

If everyone had the right to board a plane and go wherever they wanted, that would make a big difference. That would mean no more deadly shipwrecks, no more border crossings, no more need for the smugglers that everyone talks about cracking down on. In the case of refugees, that would mean possibly permanently [being allowed to stay] somewhere if there could be more welcoming policies—the way that there has been in the European Union with Ukrainians. That could go a very long way toward making life safer, better, happier, and more fruitful for people who have, to say the least, been through a lot.