In-conversation: Sarah Souli on a Triple Murder on the Greek-Turkish Border

Sarah Souli discusses femicide, migration, and Greece's deadly land border with Turkey.

At the outset, Sarah Souli had little information about the three people slain on the Greek-Turkish land border. She didn’t yet know where they were from, nor did she know how and why they ended up murdered in a field.

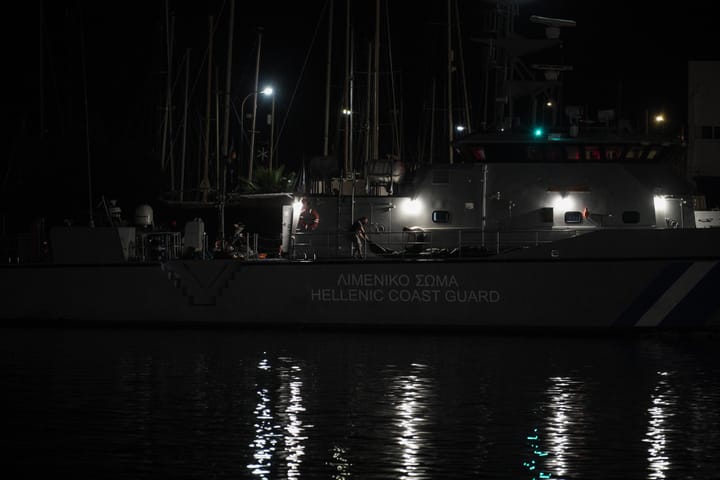

But three and a half years later, in November 2022, The Atavist published her deeply researched story of the murders. Death wasn’t uncommon in Evros—many had died crossing the border, an area that includes a closed military zone, over the years—but as she writes, “Murder, though, is a different matter.”

Titled “A Matter of Honor,” it’s a story that travels from Greece to Turkey to Afghanistan. It examines the events that led a mother, Fahima, and her two daughters, Rabiya and Farzana, to Evros, where their throats were slit.

Based in Marseille, Souli is a freelance journalist who spent several years in Greece and Tunisia. Her work has appeared in The Economist, Vice Magazine, and The Guardian, among others. Her journalism has been supported by Fabrica, the International Women’s Media Fund, the Stavros Niarchos Foundation’s Incubator for Media Education and Development, and the Alfred Toepfer Stiftung.

Since its publication, “A Matter of Honor” has won several awards, including from the Overseas Press Club and the American Society of Journalists and Authors. It was also a finalist for the Livingston Awards and an honorable mention in the One World Media Awards’ Popular Feature category.

Souli spoke with Long Road Magazine’s Fahrinisa Campana about her work reporting on migration and the years of labor that went into “A Matter of Honor.”

Fahrinisa Campana: I would like to speak more about “A Matter of Honor,” this piece that you did over the course of three years. It centers on a place where there is constant tragedy, much of which goes entirely undocumented. What is it that drew you specifically in this instance, to the tragedies that befell these three women? How did you find this story and decide that it needed to be told?

Sarah Souli: I had already been doing a lot of reporting up in Evros, on pushbacks, which now have been thoroughly documented. I should say alleged “pushbacks,” because the government routinely denies it, they engage in pushbacks. But at this point, that’s been pretty much debunked. They do happen. But at the time, there was very little reporting that was being done on that.

I was up in Evros, and I have all my contacts up there, both in terms of people who work kind of in the detention centers and people who live in the villages and see migrants crossing. I was talking to one of my contacts, and he goes, “Hey, did you hear about these three people?” I'm not even sure he knew that they were women who were murdered on the border. I was like, “No, what's like, what's that about?” He says, “Yeah … we all think that it's ISIS that that did this.” And I was like, “Okay, I was like, I don't think it's ISIS.” But, you know, murder is not something that happens often.

So, the border crossing between Greece and Turkey is obviously extremely fraught with difficulty, and there is a lot of death. I think something like in the last five years, over 200 migrants, refugees, and asylum seekers have died crossing the border. But most of those people die from hypothermia, they drowned in the river, which is the biggest natural separation between the two countries. In 2020, the Greek military allegedly shot a few refugees trying to cross, but murder is not something that happens.

I went to go see Pavlos Pavlidis, who's the forensic scientist in Alexandroupolis. He's essentially the only person who's responsible for identifying bodies. So, I knew that the bodies had gone to him. And I went interested, sort of an informal interview, and he was like, Yeah, we haven't had a murder in this region for over 20 years. So obviously, as a journalist that super piqued my my interest. And I also just felt a gross sense of injustice. These were three women, a mother and her two teenage daughters who, at the time, no one even knew where they were from. But obviously, they were from a third country. They were obviously asylum seekers. And so I knew that they had left searching for a better life and it just seemed insanely cruel that they had managed to get a few meters into the supposed safety of Europe, especially as women, and their lives were cut short in such a brutal way.

There was also very little mainstream reporting that was being done on it. I think there was one little blurb in either Reuters or BBC. And that was essentially it. And there was no follow up a year later, there was an article in Vice Greece. But there was no deep and thorough investigation. So, I decided to take the project on myself and then spent three and a half years reporting on it in Greece, Turkey, and in Afghanistan, because these women were from Afghanistan.

FC: Because you've spent so many years reporting in the Evros region, can you just describe a little bit what it's like for people crossing?

SS: The interesting thing about Greece and Turkey is that they have a historic relationship. Greece was part of the Ottoman Empire for 400 years. There have historically always been a lot of Turkish people, or people of Turkish or Muslim origin, in Greece. There are also a lot of Greeks or people of Orthodox Christian origin in Turkey. There was a huge population transfer—I think the biggest of its kind ever—in 1922. Around that time, a lot of people crossed over from Evros.

So, it's historically always been an important migration point. And the border has been militarized for a very long time. Up until 2009, the number one cause of death for people crossing was getting blown up by landmines; the whole area was still riddled with landmines on the Greek side. It’s an extremely militarized border, and [Greece has] gotten funding from the E.U. Frontex is there. There are around 10,000 or 15,000 Greek police officers on the border. And there's sort of this misconception that because it's a river—you can see the other side when you're standing in Turkey, you can see Greece and vice versa—that it's somehow safer than the sea. In some instances, it is safer, but it's also still an extremely fraught and dangerous journey.

People first have to get their way through the Turkish side, which is also a military zone. Sometimes they face a lot of harassment on the Turkish side, then they have to cross the river, which they do in boats, but it's the same thing as the Mediterranean Sea. They're pretty crappy boats; people often fall out [and] drown. The river has particular currents, and it has a very muddy bottom as well. It’s easy to get dragged down and then stay there. Then another issue is that it's freshwater. For people who die in the river, there's no salt to preserve the bodies, which causes a huge problem later on in terms of identification, as opposed to bodies that are found in the sea, where the salt sort of helps preserve them.

Then, if they manage to cross the river, they're greeted by this extreme military presence on the Greek side. They come across soldiers or police officers, who engage in illegal pushbacks by basically not allowing people to register as asylum seekers and have their cases scrutinized. They just immediately send them back to Turkey. People cross and try to get out of Evros as quickly as possible. This means that smugglers are usually organizing the journeys. And they end up taking cars or walking to Thessaloniki. One very unfortunate byproduct of all of this is that smugglers often use very inexperienced drivers. There are a ton of car accidents, of course, because these are young, inexperienced people who are driving in a very stressful situation. A lot of people die in car accidents.

FC: How difficult is it to get information, to find sources and people who know things about a place that is essentially a closed military zone on both sides of the border, and who will talk?

SS: Obviously, the police are not going to talk to you, especially up in Evros. One lucky thing about this particular story was that because … that [it] happened on Greek soil. It was such a confusing situation. So, it was a mother and her two daughters who were found without any identifying documents, they had their throat slit. The case was given to this pretty high ranking, actually the highest-ranking female police officer at the time, Zacharoula Tsirigoti. And when she came up to the scene, she brought the case immediately to the anti-terrorism department in Athens, not because she thought it was a case of terrorism, but because the anti-terrorism unit in the Hellenic Police just have the most advanced technology. They found a cell phone on the mother's body to extract metadata, this sort of thing. The police in Evros are never going to talk to you. Maybe I've had some luck, sometimes finding one rogue police officer in a coffee shop and managing to get a little bit of information. But in this case, it just wasn't in their jurisdiction anymore. I was lucky—lucky is maybe not the word—but Tsirigoti was actually removed from her post when New Democracy came to power [in July 2019]. So, it was very easy to do interviews with her because she didn't have to go through her supervisor. She was able to … give me all of the information about the case, because she was no longer with the Hellenic Police force. And then it was quite difficult to get interviews with the new police officers who are in charge of the case in the anti-terrorism unit. But I did manage to do that.

But I would say my biggest sources of information were from refugees themselves and or like, human traffickers. I did all that reporting in Istanbul in the Zeytinburnu neighborhood, which is sort of an Afghan enclave in Istanbul. And people there who are not officially part of the system … very intimately know that area, because they're the ones who are either trying to cross it or who have been handling groups like transferring groups of people across the border for years or decades. Somewhat ironically, the easiest way to find information about Evros is outside of Evros.

FC: Can you talk about how people who are crossing this region are put at an extremely elevated risk by both Turkey and Greece, and how this leads to these kinds of tragedies, like femicide, that are virtually unknown because they happen far from anyone's eyes and far from any witnesses?

SS: I would say first that femicides happen everywhere in the world. I don't think it's something that's unique just because of the military situation between Greece and Turkey in Evros. I think it's a really unfortunate reality of the patriarchal systems that we live in. And one thing that drew me to this story was the fact that in Greece, there have been quite a number of femicides that have gotten a lot of attention, as they should.

But these [three Afghan] women were not given the same level of attention. But I do think there's something to be said for what really intrigued me about this story. And the question that I kept coming up against is: Why would these women who were murdered by their trafficker … be murdered in Greece? Because I think the thing no one really likes to talk about is that human trafficking is a business, and like every other business, you protect your product. And in this instance, the people that you're smuggling are your product, so you're not going to murder them, even if they can't pay. You're going to extort them for money or kidnap them and demand a ransom from their family back home, or something like that.

What I understood as I was reporting this story was the kind of hidden or secretive nature of Evros. There is the fact that if you're a migrant crossing, there's no way the Greek police is going to help you; there's no way that Turkish police is going to help you. That level of … strange impunity, this sort of gray zone where crime can happen, makes it easier for something like this sort of femicide to happen. Because it didn't happen in Istanbul, where Turkey is essentially a police state, especially in Istanbul, especially for refugees. There isn't a lot of freedom for them, their movements are tracked, and all of this, and it’s sort of the same thing in Greece as well.

FC: You started this investigation before COVID hit. How did the pandemic affect your investigation and your reporting plan, and what other obstacles did you encounter along the way?

SS: This story was almost like a black comedy of obstacles. I got funding from the Incubator for Media Education and Development here in Athens. I remember I was supposed to go to Afghanistan around April 2020. I also remember meeting with my grant manager and being like, “Oh, what's this COVID thing?” He said, “Well, don't worry, Sarah, in like two weeks, it's going to clear up and then you can go to Afghanistan.” I was like, “Yeah, that sounds right.” Of course, we didn't know anything at the time. It became clear that COVID wasn't going anywhere and that we were in lockdown. But I couldn't just abandon the story.

So, I had to pivot. I was supposed to go to Afghanistan, to Mazar-i Sharif, which is the region in the north, just across the border from Uzbekistan, where this family was originally from, to understand what information I could find there. I had to pivot completely. I had my fixer, who's this amazing journalist in her own right. She was going to be my translator and my companion on this trip. But I had to do the reporting essentially through her, so I sent her kind of in my place, to Mazar-i-Sharif.

We were basically just on WhatsApp video for somewhere around ten hours a day for a week or two. It was really intense because the family back in Mazar-i-Sharif didn’t know that their sister and nieces were murdered. This was information that I had to share over WhatsApp Video, which makes you feel really like a piece of shit because you want to be there physically if you are going to give that sort of information. You want to be there physically in front of the other person and to have that human connection. So that was certainly one of the biggest obstacles.

The reporting that I did in Istanbul was also extremely frustrating up to the point where it was almost cinematic. I basically did shoe-leather reporting, really old school, because I had just one contact of an individual who knew these women from Istanbul. I don't know how many people I talked to—maybe 500 to 600 people. I was just showing this photo of this mother and her two daughters to everyone. It was not going anywhere until around the 11th hour. I was taking my flight the next day, and I was so defeated. I was with a colleague at the time, who is an Afghan journalist as well. And we went into this ice cream shop. He was like, “Let’s have one ice cream and just pick the mood back up.” So, we went into this Afghan ice cream shop. He said, “Let's ask one more person.” After a week of asking everyone, I was thinking, “How could I ever think that I was going to solve this or get anywhere with this story? This is ridiculous.” And we showed this photo to one guy, and he said, “Oh, yeah, I know these people.”

So, the reporting in Afghanistan and the reporting in Istanbul were sort of the two biggest obstacles. And also just having patience, knowing that this wasn't something that was going to be solved anytime soon. I would have to have patience with myself to stick with it. I thought it would be months, and it ended up being three and a half years.

FC: There is some incredibly detailed reporting in this story. In one scene, you describe how two of the women were found on their knees, facedown, and a third woman sprawled out as if she had tried to flee. In another you talk about how Pavlidis doesn't think about what the dead were like when they were alive, or what their last moments were? How did this kind of deep reporting on a tragic topic affect you? And what were some of the things you did in order to cope with it?

SS: It became very clear to me early on that I'm not a detective or private investigator or a police officer. I don't really have the emotional tools to deal with this. So, I did start going to therapy, which was helpful in terms of managing my emotions about all of this. To be honest, though, it's something that I'm still dealing with because it's not normal for women to be murdered. It's not normal. I say women, but one of the girls was thirteen. The other one was seventeen. It was two babies and their mom. And it's not normal for them to be murdered and for their lives to be cut short like that. It's not normal that it wasn't properly investigated and solved by the Greek and Turkish police. It's also not normal that there's just some random journalist who comes along and starts investigating this story.

I feel a lot of a lot of mixed emotions about it. Certainly, there's a lot of guilt, as well. Maybe this is something that some journalists grapple with as well, when you work on a story like this and it gets a lot of attention or recognition. You think, “Wow, I'm getting rewarded for someone else's misery.” There's nothing just about that, either. So, I don't really have a straight answer. I think journalism is necessary in democratic societies. But I think it's also a much more layered and emotionally complicated situation than we would like to even admit to ourselves.

I think I've been in this industry long enough — I don't do war reporting, or even that much conflict; I'm more in a space of post-conflict reporting. I'm more interested in how people deal with the aftermath of conflict — but I see that a lot of my colleagues who work on stories like this, or much more hardcore, [that] there is a lot of mental and physical unwellness. There's a lot of abuse of drugs or alcohol or sex, these coping mechanisms to deal with the amount of tragedy that we see. Because at the end of the day, it's quite voyeuristic. It's not our lives. It's not our trauma. We're reporting on other people's trauma. I think that can create sort of a strange survivor's guilt as well. But we're also putting ourselves, with our own agency, into these situations.

And it's good to feel that, you know, because at the end of the day, it reminds you that what separating me from someone in this situation is truly just the dumb luck of my birth and my citizenship and my passport. And the thing that I just always kept saying to myself, whenever I would start to feel really guilty about working on this story was like, Well, I would want someone to do the same for me, like if I was found murdered on a border. And because of the color of my skin, or my ethnicity or my gender, that just meant that sort of the institutionalized structures that are supposed to look after me, don’t. I would want someone to do this for me.

FC: These women are three examples of how easy it is to die or disappear in the Evros region without a trace. Had you not looked into their deaths. These women may have remained unidentified, justice unattained. In the piece you wrote, “one factor working against the investigation was general disinterest in the victims. Do you think the story that you wrote moved the needle at all, that anything has changed and that people have started caring about what happens on their borders.

SS: Well, I guess I should say that there are leftist feminist groups in Athens and across Greece who have historically been very mobilized against femicides in Greece, especially over the last few years. There were some individuals within this community who started taking this very seriously because I think intersectional feminism is something that's a bit new in Greece. Greece is not a country that colonized other countries. So, it doesn't have necessarily the same history with migration as … countries like France, the UK or Italy do, where there's a long history of people from other countries. In Greece, it's been a bit different. I think this concept of intersectional feminism is something that this case brought to light, and it's been cool to see that the feminist groups in Greece are mobilizing themselves to support more refugees and migrants and just generally non- Greek women.