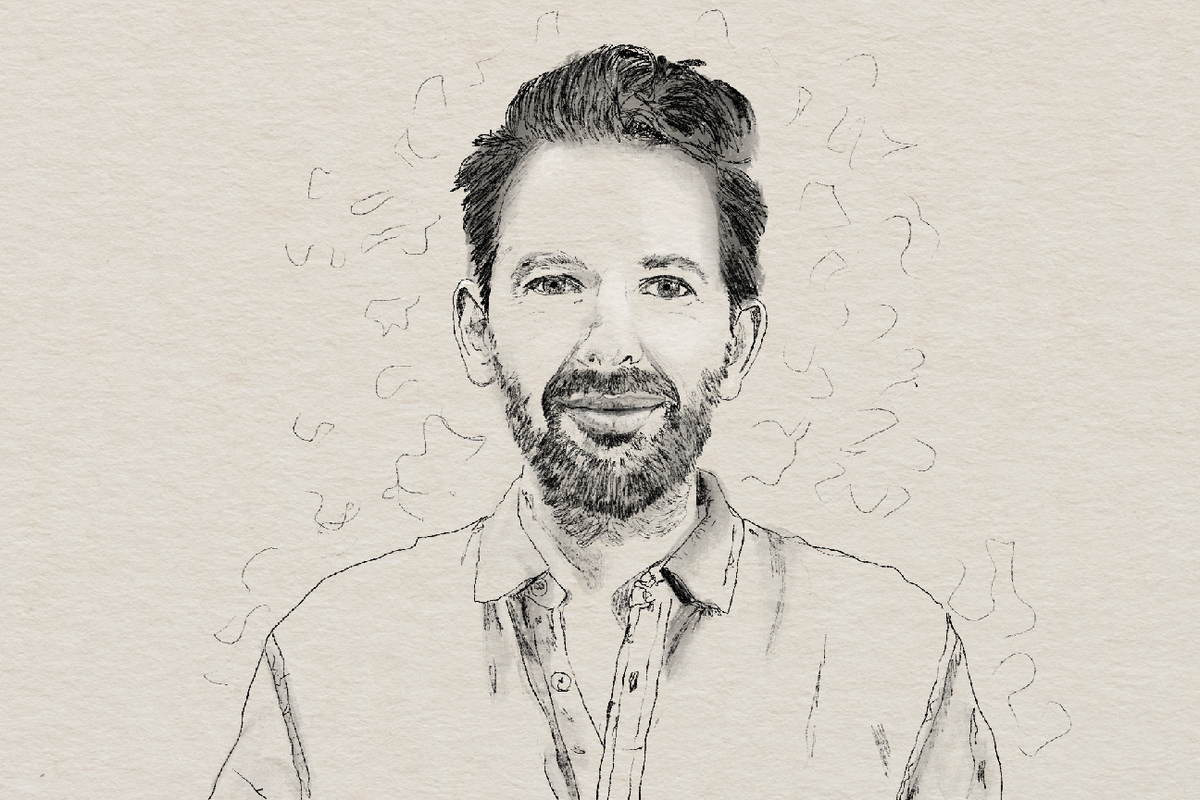

In-conversation: Antony Loewenstein on Israeli Technology on Global Borders

Journalist and author Antony Loewenstein discusses his new book, The Palestine Laboratory.

In his latest book, journalist and author Antony Loewenstein explores how Israeli technology used to enforce its occupation of Palestinian territory has been exported across borders around the world.

Published by Verso Books on May 23, The Palestine Laboratory: How Israel Exports the Technology of Occupation around the World is a grim, deeply researched book that digs into the global politics that have allowed Israel to turn Palestinians into test subjects for surveillance and military technology and Palestine itself into a testing ground.

The publication of The Palestine Laboratory comes shortly after the seventy-fifth anniversary of what Palestinians know as the Nakba, the violence and ethnic cleansing that destroyed hundreds of Palestinian villages, scattered hundreds of thousands of Palestinians outside the borders of their country, and led to the creation of the Israeli state.

It also comes on the heels of another spike in Israeli airstrikes in the Gaza Strip, the besieged coastal enclave where some two million Palestinians live.

Loewenstein spoke with Long Road Magazine about The Palestine Laboratory, the Israeli technology used on European and North American borders, and the borders Israeli forces impose on Palestinians*.

Patrick Strickland: Congratulations on the publication of The Palestine Laboratory, Antony. Early on in the book, you mention how your grandparents fled Nazism in Europe as refugees. You’ve now been reporting on Israel-Palestine for decades. How has that experience—as someone whose own grandparents fled genocide—impacted your approach to reporting on Israel-Palestine over the years?

Antony Loewenstein: As I sort of say in the beginning of the book, I don’t generally write a lot about my own personal history, but I do introduce the subject as partly in a conversation with Verso, my publisher, doing it this way for a variety of different reasons. I grew up in Melbourne, Australia, which, at the time when I was growing up in the Seventies and Eighties, had one of the highest percentages of holocaust survivors in the world outside of Israel. A lot of Holocaust survivors ended up in Australia for different reason, both in ’39 as the war was beginning but also after the war in ’45 and onwards. And I grew up in a liberal Jewish home.

For many people listening maybe who are Jewish or have Jewish friends or family, it was pretty typical then and it’s pretty typical still now that Israel is something you support. It’s something you’re expected to support, it’s something that we apparently are born into, this idea that Israel not so much as the promised land—I was never told that myth—but more as a potential escape route, God forbid, another Nazi-type regime emerges. Some listeners may not know, as a Jew and if you can prove that you’re Jewish—and the way Israel does that is very problematic for a range of reasons—but essentially if you can prove that you are Jewish, mainly your mother was Jewish, you can go to Israel and within probably two or three months, you’ll get a passport [and] you’ll be an Israeli citizen.

I don’t have an Israeli passport. I won’t get one on principle. But the idea of Israel as a safe haven was something I grew up with, and a lot of Jews did in the past and still do now. I think now it’s changing a little bit.

My family were mostly killed in the Holocaust. The vast majority did not survive, which is almost a very typical Jewish European story. They were in Germany and Austria. Many of them ended up in Auschwitz, and they were exterminated. And the ones who got out in ’39, just before the war, ended up anywhere that a country would accept them: Australia, Canada, the U.S., the U.K. None, as far as we’re aware, went to—of course, Palestine wasn’t Israel then, but it was Palestine—but no one went there as far as I’m aware.

So, that was a big part of my upbringing. I was taught all the myths. I went through all the processes: ‘We’re the chosen people.’ I mean, I speak then and now as a secular Jew. We’re not religious, and I think for many Jewish people, Israel has become their religion. It has replaced any kind of traditional religiosity like going to synagogue. Even very liberal Jews might go to synagogue on Passover or some other major Jewish holiday, but in general Palestinians were invisible. When I say invisible, in the Jewish community, Palestinians were not heard from [and] they were not talked about apart from being demonized. And of course, I grew up before the internet, which I think makes a big difference—I don’t use this as an excuse but as an explanation. It was more difficult to get the Palestinian point of view and to hear Palestinians in the media. Back then, Palestinians were largely absent, so many in the Jewish community, the Israel lobby, [and] my family demonized Palestinians [and] demonized Arabs. They were said to be the new Nazis, they wanted to kill us all, push us into the sea. Yasser Arafat, who was the then leader of the Palestinians, was deemed the new Hitler. This was the narrative. I’m not saying I entirely bought into it, but to some extent I did a little bit. It’s hard not to when you’re ten or eleven or twelve.

As time went on, I started to question it more. I felt very uncomfortable with the racism I was hearing around the family table, around the Sabbath meal on Fridays with my family. By the time I got to university in the mid-Nineties, again mostly before the internet, I started reading more widely. By the time I went to Israel and Palestine for the first time in 2005, I was researching my first book, My Israel Question. Even then my views were quite different to now. I said I was a believer in the two-state solution [and] I would have called myself a Zionist, neither of which I believe anymore. But that’s what I thought twenty-odd years ago.

PS: Of course, there are millions of Palestinian refugees spread across the map of the world, some whose ancestors were displaced in 1948, others in 1967, yet others afterward. But you also write at length about the grim prospects of African refugees who make the journey to Israel. What’s Israel’s record when it comes to Eritrean and Sudanese asylum seekers, among others?

AL: Terrible, is the short answer. Certainly, over Israel’s history there have been moments where certain African refugees who were Jewish have been accepted in not massive numbers. For example, Ethiopian Jews at various points in Israel’s history have been taken in and given citizenship. Although many Ethiopian Jews have not been and, in fact, there are a lot of other particularly dark-skinned and Black Africans and others who claim to be Jewish whom Israel has simply not accepted.

I see Israel today as really a manifestation of a form of white supremacy. And I say that because there is profound racism against Arabs, for sure, but against Africans, too. Then it comes to, for example, Eritreans, Sudanese, South Sudanese, and various other Africans who many years ago entered Israel via one of the borders, some of them feature in the book and I’ve kept in touch with some of them. Some remain in Israel. Some left because of the massive racism against them and tried to find greener pastures. One of them ended up in Germany and took a dangerous boat ride across the Mediterranean. There are lots of crazy stories like that.

But there’s profound racism. This is a level of more than racism. There’s a degree of dehumanization, of not really viewing them not just as Jewish but as equal citizens, or as equal people, that they should be ostracized and that they should be kicked out. In the last twenty years, I can’t give you the exact number, but the number of African refugees that Israel has accepted as citizens because they’re legitimately fleeing persecution is minuscule. I think it’s potentially ten if not less, I mean unbelievably small. And these are people who are legitimately fleeing from persecution—Sudan, South Sudan, Eritrea.

One of the crazy aspects that I only feature a little bit in the book is Israel in the last ten or so years has tried to strike deals with all these repressive African states to essentially bribe them. So, they go to an African migrant in say Tel Aviv and say, ‘Alright, your application for refugee status has been refused. You’re not allowed to stay anymore, but don’t worry. We’ve organized a wonderful one-way ticket to Uganda or Rwanda. We’ll give you 3,500 USD, and when you get there, you’ll be assisted to find a job.’ Initially, people thought, ‘Okay, this sounds okay.’ But it soon became clear that it was all a lie. I met a number of these African migrants who are forcibly sent from Israel to, as I said, Uganda or Rwanda. They arrive there, their passports are taken by the authorities, they’re not given jobs, [and] many of them decide to leave and try to find greener pastures.

I met some when I was living in 2015 in South Sudan, of all places. South Sudan is a warzone. It has very few resources. It’s very poor. There are not many jobs. So, the idea that you have Israel, a nation that was founded under the guise of protecting Jews after the Jewish people’s most catastrophic event, the Holocaust, and yet decades later … there has been a ramping up not just of rhetoric against Africans but an attempt to kind of almost offshore the problem, so to speak.

I’m sure many are aware that Australia has a notorious refugee policy of often forcibly sending refugees who are coming by boat to small pacific islands: Nauru, Papua New Guinea. Those nations are bribed essentially to accept those refugees and house them in incredibly poor conditions. There’s been riots and rapes and death and murder and a horrendous record. And increasingly, Australia was a model for a lot of what the E.U. and the U.S. are doing. I’m not saying European refugee policy is solely dictated by Australia—it’s not. But I’ve done a number of stories in the last years for various outlets, some of which I quote in the book, of Australia’s refugee policy and so-called offshoring: sending people to places that don’t get much media attention or media coverage and they're kind of almost invisiblized.

That’s what Israel is trying to do by sending [away] refugees—who, by the way, in any rational human country would have been granted refugee status because many of them, if not most of them, were fleeing persecution. If you’re coming from Eritrea, which is and has been for decades a repressive state that was forcing particularly young men into conscription to fight an insane war against Ethiopia, a lot of people fled and rightly so. The idea that someone like that, and I met some of them in South Sudan and in Israel, are not granted refugee status is absurd. But that’s what Israel is doing. And there’s very little opposition in Israel to that.

Of course, there are some Israeli Jews who oppose it, absolutely, and some Palestinians for that matter, but in general it’s supported. Expel them, get rid of them, send them back to Africa. It’s not our problem. It is partly because of racism and partly because a lot of Israeli Jews who are much more hardline—which I would argue is probably the majority—don’t want Black-skinned people in their country. They openly say it. It’s not me guessing. You have huge numbers of people … rabbis and politicians and activists saying this. It’s pretty shocking for a Jew, I have to say. It’s pretty shocking.

PS: You write of Israel’s relationship with Myanmar and its arms sales to that country. You also write about Israeli arms sales to South Sudan, for instance. How would you characterize Israel’s involvement in crises of displacement around the world in recent years?

AL: South Sudan is an interesting example. South Sudan is mostly ignored in much of the Western media, and I say that having lived there in 2015. Often, trying to get media interest was challenging, to put it mildly, by Western media outlets. But I think Israel sells weapons for principally two reasons. One, for the obvious reason. It’s a money-maker; it’s capitalism. That’s why the U.S. sells arms, why France does, [and] why a lot of nations sell weapons. They do it to sell money and to get influence I guess in the hope that by selling weapons to nation X or nation Y, their country will thank them in different ways. What does that mean? It could be voting at the U.N. in a certain way, which is what Israel often hopes or pushes for when they make these kinds of dirty arms deals, but I think there’s also something else.

When we’re talking about weapons here, it’s everything from rifles … to something much more: spyware, missile defense shields or a range of other tools, so-called smart walls, facial recognition, biometric tools. There’s a range of things. … [In] Rwanda, during the genocide—there was evidence that Israel was selling weapons to the regime during the genocide.

Myanmar was committing genocide in around 2016 [and] 2017 against the Rohingya Muslim population, many of whom were either killed or forcibly kicked out to Bangladesh, and that’s kind of where they are now in this never-ending nightmare limbo. Israel was sending forms of spyware and other kind of weapons, rifles, etcetera. And in the U.N. report about that genocide, where it was called a genocide, Israel was named as contributing to that.

On the face of it, you might think that’s pretty outrageous. And what happens? Nothing happens. Now, when I say nothing happens, [I mean] Israel hasn’t really changed its policy towards selling weapons to these states and there are countless others. I list them in the book and go into some detail so that people really get a sense of the scale of it. [It happens] at pretty much every corner of the globe, South and Latin America, Africa, Asia, and democracies.

I’m not just talking about dictatorships, although obviously I’ve just listed dictatorships. They sell a lot of weapons to other nations too, to so-called democracies. And these weapons could be spyware, hacking tools, getting access to people’s iPhones or Android phones. So, I mean what’s the ideology behind it? Money, influence, and also, some of it is also [about] trying to foster a global community of likeminded nations. And that’s important. So, when, for example, Israel sells spyware or hacking tools to South Sudan, it’s not really a likeminded nation doing it because they want influence in the world’s newest nation, and they maybe hope that South Sudan will vote with them in a certain way at the U.N. when a vote comes up about settlements or some kind of policy. So, there’s not really an ideological alignment there beyond a transactional friendship or relationship.

But when it comes to countries like India or Hungary, then it’s a bit different. India is obviously the world’s biggest nation now population-wise, a self-described democracy, run in the last ten years or so by Prime Minister Modi who is frankly a Hindu fundamentalist building a Hindu fundamentalist state. Muslims are discriminated against. I’m not arguing that India is doing all of this because of Israel. Of course, that’s not true, but … they openly have senior Indian officials who admire what Israel is doing in the West Bank, namely bringing in extremist Jewish settlers to kick Palestinians off their land. That’s what [Indian officials] want to do in Kashmir. Kashmir obviously has been a flashpoint for decades. It’s a Muslim-majority area, and what India is increasingly doing in the last years is bringing great numbers of Hindus from the main part of India, the mainland, to try to dilute the Muslim population. And that is inspired by Israel. Undeniably it is. Indian officials say it themselves. So, arms trading can be, yes, transactional, brutal but transactional. But increasingly, I think, Israel is trying to build a kind of loose, unofficial coalition of likeminded states.

Hungary is another one. Hungary is obviously a relatively small country. But Orbán, its leader, has a disproportionate influence in Europe and is very close to Netanyahu and Israel. … [He] believes that he wants to create a kind of Christian ethno-state. He’s continuing to do that, and the world is pretty much standing by while he does. That impacts his refugee policy, his border policy, all those issues. And he’s not just close to Israel; he has bought a lot of Israeli technology, spyware, [for] spying on Hungarian dissidents and journalist and human rights workers and all those kinds of people—critics of Orbán essentially or Orbánism.

More and more countries are finding that … Israel is the ultimate ethno-nationalist model. It’s been going for three-quarters of a century. It has complete global impunity. No one is stopping it. No one is doing a damn thing, and it’s now the tenth biggest arms dealer in the world, which is not bad for a massively tiny country. A lot of countries look to Israel as an inspiration. That might not be what a lot of [people] think is sane. I certainly don’t think it’s sane, but I can see why a lot of nations do view Israel in that way.

PS: Since 2015, a growing number of refugees and migrants have made it—or tried to make it—to Europe. In recent years, border violence has skyrocketed, with countries across the European Union’s external borders carrying out pushbacks, or extrajudicial expulsions. How is Israeli technology being used in the surveillance of refugees and the militarization of European borders?

AL: A lot of what Israel sells and promotes is what they call ‘battle tested.’ They openly say it. ‘Battle tested’ means it’s been used in Palestine, over Palestine, or on Palestinians. So, yes, a number of drones, the Hermes drone and the Heron drone, both Israeli drones, have been used over Gaza and over the West Bank, sometimes armed, sometimes not. And they’ve been used for years by Elbit, one of the main companies, Israel’s leading defense company. And that is part of the sales pitch.

You have European nations, the E.U., Frontex (the border so-called security apparatus), and the U.S., who find it very appealing that it’s been used in Palestine “successfully.” So, in the last years, and this of course massively accelerated after the so-called refugee crisis in 2015, I mean I would argue it wasn’t a crisis. It was a created crisis, but how it was reported and how many European nations eventually saw it … was they didn’t want a repeat of that. They did not want any kind of repeat of huge numbers of Brown, Black bodies trying to enter the E.U., coming from Syria, Afghanistan, Iraq, [and] Africa in those kinds of numbers. I think there was roughly I think a million mostly Muslims who came into Germany in 2015 and of course other people, refugees, went to other nations in Europe so the EU made a pretty clear decision that they were going to frankly I would argue ghettoize themselves as much as possible —and there were a range of ways they were trying to do that of course, and you’ve reported on some of that very well so I won’t repeat all of that now.

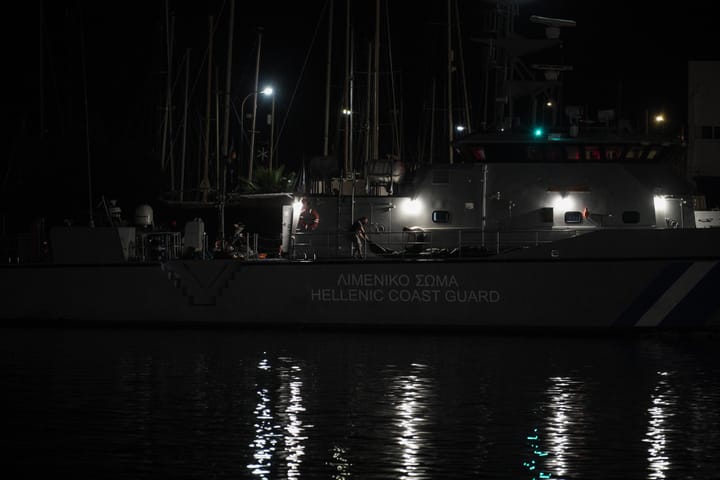

But the Israeli connection to all of that is that the E.U. and Frontex uses Israeli drones to monitor parts of the Mediterranean 24/7, every day of the year. These drones are not armed. They’re unarmed, but they are essentially the eyes in the skies. And the reason why that’s relevant is that of course the E.U. in the last years has made a very clear policy decision. Of course, they don’t admit this or acknowledge this, but this is the reality. They’ve decided they want to let people drown and die in the ocean.

You cannot get a more cynical, brutal policy than that. In other words, they’ve done that by essentially not just trying to criminalize rescue boats from taking people out of the water to take them to dry land and safety and be processed, etcetera. But they are actively advocating people either being left to drown—and the Israeli drones are the eyes in the skies that allow Frontex to see who is on the water, where they are, are they in trouble, do they need help. And in very, very few cases, help is sent but in the vast majority of those cases people are then taken, if they’re lucky, to one of a handful of European NGOs. … Seawatch [is] one of them I talk about in the book, who are, of course, massively outgunned. They’re just rescue boats, and I admire what they do hugely. I think they’re inspiring, but they can’t exactly monitor the Mediterranean. They have a handful of boats. And the people whom the E.U. [does rescue often are given] to the Libyan coastguard to be taken to Libya, which essentially has slave auctions. This is the reality of E.U. border policy, and as you say, pushbacks are part of that. Israel plays a key role in this, a key surveillance role.

The E.U. is Israel’s biggest trading partner so when … you find people saying the Europeans are pretty critical of what Israel does, mainly in Palestine, it’s a fig leaf. It’s all nonsense. Yes, sometimes the E.U. puts out a statement that they’re very disturbed about settlements. Maybe a few other western European nations occasionally put out stronger statements. But ultimately because the E.U. is based on consensus, and the consensus is that you want to keep refugees out, that’s what wins in the end.

There are European nations that are more critical than others. Hungary and Poland obviously are madly pro-Israel. A nation like Belgium is a little bit more critical, but overall, there’s no consequence for Israel’s actions. So why wouldn’t they use Israeli surveillance technology over the Mediterranean? This is a border so-called enforcement policy that is deeply inhumane, so why not use an Israeli drone that’s been used over Gaza in a number of wars in the last ten or fifteen years? It makes sense in that very kind of skewed, perverted way.

PS: The controversial Title 42 policy only just expired in the United States, and Republicans around that country are once again ratcheting up anti-migrant rhetoric and demanding further militarization of the U.S.-Mexico border. Of course, it’s already one of the most dangerous borders in the world. You discuss in the book how Israeli companies have provided surveillance technology to U.S. border authorities. What does that relationship look like in practice?

AL: In recent years, Elbit, which is Israel’s biggest defense company, has installed (and as far as I understand, they’ve been finished relatively recently) dozens of surveillance towers on the U.S.-Mexico border. They’re highly sophisticated to obviously detect migrants or Native Americans. And the reason the Native American part is relevant here is that often these are put on Native American territory without their full consent, so there are huge issues around that. What’s important also to note are two things: one, the U.S. wanted their technology again because Elbit has built similar kinds of surveillance technology and towers in Palestine across the West Bank and on the so-called Israel-Gaza barrier. And secondly because this is really a bipartisan issue in America. People rightly got incredibly angry (on the left, at least) with Trump’s immigration policies—and obviously I shared that anger—but these issues haven’t gone anywhere now that Trump has gone.

And in fact, a lot of these policies frankly started long before he was in office and have continued long after he is gone. Biden in some ways is deepening this, deepening this over-reliance on so-called border tech—massive surveillance technology, Israeli and others. So he’s not sort of celebrating as Trump did this, “Let’s build a wall.” There is still wall there, and there is still actually parts of the wall that are being built despite not reading about it that much in the press. But the majority of what Biden is doing on the U.S.-Mexico border is installing huge amounts of surveillance technology, surveillance towers and a range of other things. It’s not something that ever gets talked about much. I mean, it’s not a secret … but it seems again a really interesting case of the U.S. turning to one of its closest friends, Israel, for advice and hardware and installation of technology and surveillance that was used to “effectively” in Palestine. Again, that’s how the “Palestine laboratory” works. It’s tested first there, and then exported [abroad].

*This text is a partial transcript of an interview with author Antony Loewenstein. The full interview can be heard on the ‘In-conversation with Long Road Magazine’ podcast, which is available on most podcast apps. The text here has been edited for brevity and clarity.