In-conversation: Melissa del Bosque on the Dangers of American 'Border Theater'

Journalist and author Melissa del Bosque discusses American borders and the GOP's anti-migrant push.

In her 2017 book, Bloodlines: The True Story of a Drug Cartel, the FBI, and the Battle for a Horse-Racing Dynasty, longtime border journalist Melissa del Bosque tells in granular detail the story of the FBI’s investigation into a brutal drug cartel leader named Miguel Treviño and his elaborate money-laundering operation. A sharp work of narrative nonfiction, Bloodlines looks at the way people profit and perish on both sides of the frontier thanks, in part, to obsessive American border policies, the country’s seemingly endless appetite for drugs, and the cartels’ willingness to satisfy that demand.

It’s a detailed, multilayered story, one that reflects the type of in-depth reportage del Bosque has produced with impressive consistency for more than two decades. I first met del Bosque in Austin in 2016, when she was a staff reporter at the Texas Observer, where she spent more than a decade filing dispatches up and down the border. In the years since then, she’s reported for Harper’s, The Guardian, The New York Times Magazine, and The Intercept, among others. More recently, she teamed up with fellow reporter and author Todd Miller on The Border Chronicle, a weekly newsletter that runs reportage, commentary, and audio pieces.

Long Road spoke with del Bosque about her work on the U.S.-Mexico border, the dangerous those who make the journey face along the way, what she and others have termed “border theater,” and what to expect as anti-migrant politicians ratchet up cynical claims of a supposed “invasion.”

Long Road Magazine: If I recall correctly, on your website it says you started reporting in 1998, that’s right?

MELISSA DEL BOSQUE: Yeah, back in 98’ pre-9/11 I started reporting on the border. [I] decided that I wanted to be a border reporter when I was living in San Francisco, California, so came out to Texas, went to University in Austin and that’s sort of where I started traveling to the border—the Texas/Mexico border—and reporting there.

LRM: Yeah, that’s actually where you and I first met, though it was sometime later and that’s something I was going to ask about as well. I mean, you spent the first part of your journalism career based in Texas for quite a long time and over the years you reported pretty extensively on both sides of the line. I wanted to ask, if when you speak to people now about what they face along the way, people who cross the border, do you get the sense that it’s become more dangerous?

MDB: Oh yeah, it’s become infinitely more dangerous. I mean, when I first started reporting in the late 90s and pre-9/11, especially in Texas, the communities on either side were pretty fluid going back and forth. The communities were a lot more connected—the border communities—and I would go over to Mexico and do reporting. I worked for a daily newspaper in McAllen, Texas, which is a border town down at the tip of Texas. The feeling was that there was danger, of course, that there were drug traffickers and things going on, but that it wasn’t as dire as it is now. And really what has made things more dangerous, ironically, is this building of this border security industrial system. You’ve got walls, you’ve got armed border agents, you’ve got drones, you’ve got ground sensors, you have all this various technology that’s been put in place to deter people from crossing, which hasn’t actually worked. What it has done is just made it much more lethal to cross. And it’s also really empowered organized crime [groups], which are now making billions of dollars off of crossing people and extorting them. It’s created this huge industry and has really made it a lot more dangerous for people to cross.

LRM: Building on that point, I wanted to ask also about the challenges of actually reporting on and from the border. You mentioned the militarization of the border and building this massive, hyper-inflated security apparatus on the border that’s made it much more dangerous for people to cross. Has it also made it much more difficult to report in the borderlands?

MDB: Oh, yeah, absolutely! You know, just your movement is so much more limited now. Mexico has been experiencing this crisis of violence now for many years, which really started to come to a head in 2006, when the former Mexican president, Felipe Calderón, sent the military out into the streets to fight drug traffickers. That really came to a head in Ciudad Juárez right there on the border across from El Paso, and then also in Nuevo Laredo, also across from Laredo, Texas. It really plunged communities there into these really spiraling death rates with the military extrajudicially killing people and disappearing people. Instead of the military going out and making things safer, they made things infinitely more violent and dangerous. The police are also involved as well, so Mexico has really been experiencing this low intensity war for almost two decades now. It’s been a total challenge for Mexican reporters, many of whom have been targeted and killed for reporting on the nexus between drugs traffickers and politicians—you know ‘narco-politics,’ they call it, which has really become a big problem in Mexico. And, so, journalists there have really had to learn how to report in this very, very difficult environment where there’s war-like violence going on but it’s not an actual defined war. And then on the U.S. side, we’ve had this huge buildup of, as I said earlier, walls, armed guards, police, especially in Texas now with the Governor Abbott saying that he’s sending ten tanks to the border now—he’s already got soldiers down there. So, it’s this completely outsized response, which has really churned border communities, especially on the Texas side, into these sorts of police states where people are continuously stopped and harassed, and constitutional rights are completely trampled. So, there’s heavy-handed police enforcement and surveillance that’s happening on the US side of the border.

LRM: If I recall the year correctly, I think even back in 2015, long before Texas Governor Greg Abbott had launched his Operation Lone Star, you had a piece at the time that specifically kind of talked about how border authorities in the area constituted, for many communities, an occupation in effect.

MDB: That’s been ongoing now for years. What’s always bothered me about that—you know, I lived in Texas, you’re from Texas, and I reported on the Texas-Mexico border for twenty years—is that the rest of the country tends to think of Texas as well, ‘That’s just Texas, that’s their problem, it doesn’t have anything to do with the rest of the United States.’ But the Texas border is the majority of the U.S.-Mexico border, and it does reflect on our country as a whole in the way that we treat people who are coming to request asylum. It shows the rest of the world what our values are and what we’re about as a country. What Texas does has a lot of impact internationally in the way that we’re perceived by the rest of the world. I wish the rest of the country and Washington would pay more attention to what’s happening at the Texas-Mexico border. Right now, as we see with this escalation under Governor Abbott—he’s just won re-election now and it’s his third term—and the first thing he did after winning reelection is declare an invasion on the border and say that he was sending ten tanks down there. He’s just going to continue to ratchet up this dangerous invasion rhetoric, which characterizes asylum seekers as literally an invading army. And these are U.S. communities where we have some of the lowest crimes rates in the country, and that’s been that way for years. There’s not a war going on, but he continues to portray it as this war zone for Fox News and rightwing publications who then magnify his message, which is, at its heart, a racist message and a xenophobic message. And, really, I think what voters showed us during the midterm is that they don’t buy into this xenophobic, racist message that Republicans went all in on and invested millions and millions of dollars on —he invasion rhetoric and the “Great Replacement Theory,”—which is this white supremacy theory that Democrats and Jewish people are allowing Brown and Black immigrants to cross the borders so that they’ll vote for them. Just ridiculous stuff, which they completely made their platform and invested millions and millions of dollars in campaign messaging around. But it was rejected in a major way, which is really encouraging because our country is saying, ‘No, we’re not going down that road.’ Yet, we continue to have Greg Abbott, who is going all in on the invasion/Great Replacement rhetoric. And we have Governor DeSantis in Florida, who is also going down that route. So, I think we’re going to see those two really going back and forth down that spiral of how xenophobic and racist in their rhetoric they can get.

LRM: Right, and Operation Lone Star, as a state-led crackdown, is really interesting in a sense, because from everything that I can tell, it’s not very effective at what Greg Abbott says it’s doing. And there are all these different elements of busing people to sanctuary cities like Chicago or D.C. or New York, or deploying Texas National Guard and Department of Public Safety agents down to the border in massive numbers. Have you gotten the sense that it has in any way, from Greg Abbott’s starting point of trying to slow down or deter migration, been effective at all?

MDB: No. Just recently Border Patrol’s own statistics show that there are still more people coming. It hasn’t deterred people from coming. The US government has been practicing deterrence, this prevention through deterrence as they call it, since the mid-‘90s and putting up walls and putting out armed guards and making it increasingly dangerous for people to cross so that they have to go to really remote and dangerous places, like the Sonoran desert to cross. So, since prevention through deterrence was started by the U.S. government in the ‘90s under Clinton we’ve just seen the number of deaths escalate of people trying to cross. The United States has been down this road with prevention through deterrence and trying to just make it so awful and so deadly for people that they won’t come. That doesn’t work, because people are fleeing situations far more dire—climate change, they’re fleeing gangs, political violence—and so people are in a situation where they have no choice so they’re going to come. And the question is now—and this is happening all around the world where we’re seeing an increasing number of displaced people due to climate change and other issues—is at some point the U.S. government is going to have to come to terms with this, that this is the new normal. We’re going to continue to see large influxes of people arriving and seeking asylum. And we just haven’t had an asylum system all throughout Trump’s era. He basically shut it down and it’s never been reopened, because the Biden administration, despite his campaign saying that they were going to create this whole new border policy that was going to be humanitarian and so forth, they didn’t do any of that. All he did was keep Trump’s policies in place, like Title 42. And so now, a federal judge has announced that they’re going to lift Title 42, but now it’s been put on hold for another five weeks and there’s this huge bottleneck of people in Mexico from all over the world who have been waiting, some people for years, hoping that they can have a chance to ask for asylum. That is what is waiting for us now, and it’s going to be very interesting in the next few weeks to see what the Biden administration decides to do, if they will set up a more humanitarian processing system, or if they’re just going to put up more deterrence. Of course, Greg Abbott in Texas sending the tanks to the border and all that is in response to Title 42 ending, because he’s going to go all out on the xenophobic rhetoric and war-like imagery, which we’ve already seen doesn’t work.

LRM: Since Joe Biden came to office, conservative media has played what seems like a prominent part in drumming up fear over the border, and this sort of border paranoia. Earlier this year, Fox News ran a piece about migrants allegedly killing people’s pets while coming over the border, and they cited people in Eagle Pass without last names attributed to them. I called the police station in Eagle Pass, and I called the county sheriff there, and they said, ‘No we don’t have any reports of that sort.’ Shortly after that, I belatedly came across your piece about selling chaos at the border, as you phrased it. And something that was interesting in that piece that you mention is that there’s basically a livestream broadcast from the border on Fox and other rightwing outlets right now. Do those sorts of images and stories, that constant stream that paints a picture of mayhem on the southern border, clash with what you see when you actually go out there and report and speak to people?

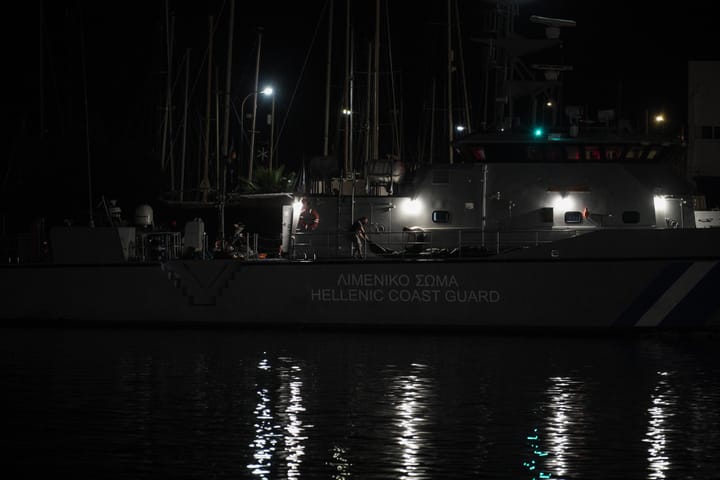

MDB: It’s completely contrary to what you see on the ground when you actually go in person. But it’s been very interesting. Since Biden took office, Fox News has had several camera crews full-time at the border, stationed there, especially in Texas where they’ve fed off the imagery that Abbott has funded now with four billion dollars of taxpayer money. He’s lined up Humvees with National Guard soldiers with their guns facing the Rio Grande all in a line; he’s put up the shipping containers, doubled up along the river with [concertina] wire along the top; he’s done all kinds of these very visual types of setups purposefully for the TV cameras, like Fox News, because they feed off each other in a loop. And this has been going on, to some extent, for many years. People in border communities call it ‘border theater’ because it’s a visual, symbolic measure that’s being done for political reasons. It’s being done for television and for social media, but it’s not being done for border communities or for the migrants or for the overall issue, which needs to really be tackled and solved. The issue is what we do about asylum seekers arriving at our border. Do we have like actual programs that work or not? Abbott and some other politicians are not interested in a solution. What they’re interested in is winning the next election, and the border, for Republican primary voters, is a huge issue, and it does win Republican primaries. So, as long as they can continue fear mongering on the border and using that as a wedge issue and winning primaries with it, then they’ll continue to do it.

LRM: Throughout the entire midterm election season, the border was one of Greg Abbott’s main talking points. Where you’re at now, in Arizona, it was also one of GOP gubernatorial candidate Kari Lake’s main talking points: the so-called invasion at the border. In a recent interview with Marianna Treviño Wright of The National Butterfly Center, which has played over the years an important role in opposing the border wall, you pointed out that Greg Abbott is—once we have this new incoming group, thanks to Katie Hobbs’ victory in Arizona—the only Republican border Governor to remain. What do you think the impact though of all that rhetoric could be in a longer term?

MDB: It’s a battle of diminishing returns. The Republican Party in Texas has really dug in its heels on this great replacement and invasion rhetoric, this really ugly white supremacy type of rhetoric, which is going to impact them very negatively in the future. Texas is a diverse state, and it’s becoming increasingly diverse and majority Latino. And for them to keep fear mongering on the border like this, and using this very racist language against Latinos, is ultimately going to backfire on them. In Texas, the lieutenant Governor, Dan Patrick, has gone on Fox News and equated asylum seekers arriving at the border with Pearl Harbor, that it’s that kind of attack, that it’s that dire that we need to fight back and use such over-the-top rhetoric. This does have an impact, a horrible impact, like we saw in El Paso with the horrible massacre at the Walmart there where the gunman, a young white guy from North Texas, drove all the way to El Paso purposefully to target Latinos because of the ‘Hispanic invasion.’ And he parroted the same language that Patrick and Abbott regularly use. So, it has real-life and very deadly consequences.

LRM: Certainly, and if I’m not mistaken, Greg Abbott at the time of the El Paso mass shooting even condemned that type of rhetoric. That does also bring me to another recent piece of yours where you broke down some of the reporting about a shooting in Hudspeth County out in West Texas. In that shooting, if I’m not mistaken, it was two brothers who went out and they shot and killed a man named Jesús Sepúlveda Martínez, and they injured a woman named Brenda Berenice Casias Carrillo. In the past, you also reported on anti-migrant violence quite a bit, including on far-right militias. You went and met Kevin "KC" Massey’s militia group, Rusty’s Rangers, in South Texas. You also reported on the institutional violence. You wrote an important piece about a Texas Department of Public Safety’s helicopter involvement in a sniper shooting that killed two men in Hidalgo County. Do you get the sense that these sorts of violent incidents are becoming more common, or is it that they’re more thoroughly reported on?

MDB: Well, I mean, in that piece that I wrote, I titled it, “Racial Violence Haunts The Border,” and I was making the point that Hudspeth County, where these two twin brothers, a couple of older white guys, shot at a group of migrants killed one man and injured another woman, that the very county is named after Claude Hudspeth, who was in the Texas Legislature, who used to go out and say, ‘We need to kill more Mexicans before they kill us.’ The history of Texas being colonized is a very violent one. It’s always been unsafe for Indigenous people, for people of color, since white settlers arrived in Texas. There’s a circular nature: There is this violence that is always there, that can be touched and can be resurrected through xenophobic rhetoric from state leaders. And the stuff that Donald Trump was tapping into is very old in our country, unfortunately, and it goes back to the founding, the colonizing of America and the wiping out of Indigenous people, and also excluding the Chinese. It’s always there, basically, and it can be resurrected. Political violence is used and resurrected very intentionally, I think, by elected officials. Though they might pretend it’s not intentional, it is.

LRM: I mentioned Kevin “KC” Massey. He was an important figure in the anti-migrant militia movement. Of course, he’s since died, but it brings to mind a recent story you wrote that really interested me. It was about the vigilante movement on the Arizona-Mexico border and their rhetoric becoming cloaked in humanitarian language. I’m curious what you make of that and why that’s changed. KC Massey, I believe when he spoke to you, he said frankly, ‘We want to stop so-called ‘illegals’ from coming across.” What do you make of the shift in their rhetoric?

MDB: It’s really interesting. What I’ve noticed is that the rhetoric now has also really merged with the QAnon conspiracy theory, and QAnon is very much obsessed with child trafficking—that the children coming across are being trafficked either for their organs or for sex, you know, There’s this very dark vein to their conspiracies. So that has been adopted by some militias where they’re now ‘humanitarian.’ They see themselves as humanitarians rescuing these children. But at the same time, they’re very heavily armed. They’re wearing ballistic vests; they’re wearing Punisher skull regalia. They look really scary. When they talk, they’re sort of merging with this Christian Evangelical thing too, where they’re Christ’s messengers, or the hands and feet of Christ, as one militia refers to themselves from North Texas. It also, in a very cynical way, has to do with fundraising, because they’re all fundraising. They’re all on Gift & Go and different platforms, and so if they characterize it as this Holy Crusade and calling, and this humanitarian mission, then it’s going to be a lot easier for them to raise money and to continue basically harassing and scaring people at the border.

LRM: Yeah, it’s certainly interesting. The North Texas militia you’re talking about is the Patriots for America Militia?

MDB: Exactly. Patriots for America.

LRM: I’ve read some of their fundraising appeals, and in some of it they really focus on the assertion that they’re just a Christian group that goes out to try to save the children and so on. That is a strange shift within that broader movement. In some of their fundraising calls I’ve seen, there were some blatant dog whistles like, ‘We have to stop the Haitians from coming across the border,’ which is obviously a little more revealing. But they’ve gotten the kids’ gloves treatment in Fox and other media outlets. They’ve gotten some nice profiles that made them look like pretty decent folks.

MDB: Right, but you know they were there for the January 6th [riot] at the U.S. Capitol. If you scratch the surface, it’s a much more violent movement. They’re heavily armed, and they’re walking around in ballistic vests, and they’re also very paranoid that the cartels are after them. They really ratchet up that rhetoric as well, which helps them raise money also. So, it’s also interesting how these fundraising platforms and social media are changing … militias’ messaging around what they’re doing. But when you go and actually see what they’re actually doing, it’s like, ‘Okay, well, they’re just scaring the crap out of people, basically.’

LRM: Has the type of story that you gravitate towards as a reporter changed over time or do you feel that changing now? You recently traded Texas for Arizona. Have your interests within the broader scope of border reporting shifted at all?

MDB: The landscape is much more complicated now. And what continues to really interest me and fascinate me is how imagery of the border is used for political reasons by the rightwing—how they fear monger and how they take these images and they use them for their own benefit, much to the detriment of the actual communities, this border theater that’s happening, because I would say that in the United States there’s probably not a region that’s more talked about, more debated, than the border. With misinformation and disinformation, the border is talked about all the time, but it’s completely and totally misrepresented constantly. We’re talking about millions of people who live along the border. It’s a huge region with some big cities like San Diego or Brownsville. It’s not just some backwater. It’s actually a good portion of the country, but it just continues to be completely misrepresented and lied about, which angers me. I also just find it fascinating how they manipulate the imagery and the message around the border.

*This conversation has been lightly edited for brevity and clarity.