In-conversation: Nada Homsi on 'Death Boats' and Anti-Refugee Sentiment in Lebanon

Journalist Nada Homsi discusses Lebanon's surge in anti-migrant sentiment and the dangerous journeys refugees risk to leave.

Nada Homsi has been reporting on refugee issues, migration, and borders across the Middle East since 2015. She’s worked for The New York Times and NPR in the past, and she’s now a Beirut-based correspondent for The National.

In recent months, Homsi has written several dispatches about a wave of anti-refugee sentiment in Lebanon, informed by the country’s long history of animosity toward displaced people and now fueled by several parties’ resort to conspiracy theories and xenophobia against Syrian refugees.

With a population of around six million people, Lebanon currently hosts more than a million Syrian refugees who fled years of war and economic devastation in their country, according to the United Nations refugee agency, or UNHCR. Since April, Lebanese security forces have detained more than 800 Syrian refugees and deported at least 336, according to the Access Center for Human Rights.

Homsi spoke with us about her reportage and the experiences of refugees and migrants in Lebanon in recent years.

Patrick Strickland: You’ve been reporting on refugee issues for several years, many of them in Lebanon. What’s the situation like for refugees in the country right now? What have some of the people you’ve spoken with told you about their lives in limbo in Lebanon as a fresh wave of anti-refugee sentiment washes over the country?

Nada Homsi: The situation in Lebanon is generally horrific for most people—Lebanese and Syrian alike—due to the economic crisis. The middle class has essentially disappeared, which means the perceived competition between refugees and Lebanon’s citizens has heightened acutely since the start of the crisis. Especially lately, political scapegoating of Syrian refugees has escalated, encouraging an environment that is generally hostile to refugees. Refugees might have an impact by somewhat exacerbating the economic crisis, but they in no way caused it; it was bound to happen.

The anti-refugee, and specifically anti-Syrian, rhetoric is so high it dominates conversations in streets, cafes, taxis. Almost everything is blamed on the refugees—including street traffic, believe it or not. A lot of the hostility is based on misperceptions and misinformation caused by political fear mongering.

Of late the Lebanese army has taken to conducting home raids on refugees throughout the country. Since April, they’ve arrested over 800 people and deported more than 330 people to Syria, which puts refugees at risk of persecution by the authoritarian Syrian government, opposed by many of those who sought refuge from the war in Syria.

The deportation campaign and the hateful rhetoric has created a very hostile environment for Syrian refugees. Many people I’ve spoken to over the last two months have expressed anxiety at staying home, fearful of more home raids and choosing to instead stay in the homes of relatives or friends.

Others are anxious to be out in public, afraid of checkpoints or being stopped simply for “looking Syrian.” This would lead to authorities checking their documents and, again, potential arrest or deportation as many Syrian refugees have expired residency or no residency at all due to the bureaucratic difficulties involved in getting it.

The hatred against Syrian refugees has even transformed into a hate against Syrians in general. This is because the Lebanese government in 2015 asked UNHCR to stop registering refugees, which has made it difficult to distinguish refugees from expat Syrians in Lebanon.

On a personal note, when in public in certain environments I’ve lately become hyper-aware of my obvious Syrian accent, afraid of hostile stares and comments or escalations. I’m cloaked by my American citizenship, am relatively privileged, and I’m not a refugee, so you can imagine what the environment is like for refugees who are not cloaked by such safety mechanisms.

PS: Lebanon has a long history of cracking down on refugees, for instance Palestinians. What’s driving this current spike in anti-refugee sentiment, and do you see that history informing the kind of xenophobia pushed by many politicians today?

NH: Lebanon has a complicated history with refugees. When Palestinian refugees, most of whom are Sunni Muslims, came to Lebanon after they were displaced in 1948 and 1967, there were fears their prolonged presence would tip the state’s delicate sectarian scale and that Lebanese Christians would become a minority. Again, this is all political scapegoating because it’s predicated on the notion that if Muslims overtake Christians, then Lebanon won’t be Lebanon anymore.

The country also has a history with neighboring Syria, which was a warring proxy in Lebanon’s own 15-year-long civil war, and which maintained a military presence long after the war’s end. The Syrian government withdrew its military from Lebanon in 2005, but its occupation has left a negative association in the minds of many. Now, with the UN estimating more than a million Syrian refugees in Lebanon who are also mostly Sunni Muslim, there are again fears the sectarian balance could be tipped.

Basically, politicians have exploited what were already some negative associations against Syrians within certain communities and exploited sectarian fears. Add to that fears among Lebanese that the significant refugee population would lead to competition over jobs and resources.

These factors have all come together to create an atmosphere of discrimination routinely faced by Syrian refugees. That’s part of what’s been driving the current anti-refugee hate. There’s also the economic crisis which is widely attributed to the state’s flawed financial system.

Since 2019, Lebanon has been undergoing what is one of the biggest financial meltdowns in modern history. Politicians—many of them former sectarian warlords—have done very little to bring the country out of the massive economic crisis.

Meanwhile, a presidential vacuum that’s left parliament paralyzed has persisted for the last seven months, leaving only a resigned, impotent caretaker government in charge. This means the numerous reforms needed for economic relief are not forthcoming anytime, and neither are solutions to ordinary people’s hardships.

In the meantime, as the state continues to disintegrate on almost every level, deflecting the blame onto Syrian refugees has proven an easy and successful tactic.

PS: What about the demographic replacement conspiracy theories you’ve reported on? Are those capable of putting people like Syrians and Palestinians at even more risk in a country where they already face so many hardships?

NH: Much of the hostility is based in the misperceptions and misinformation caused by political fearmongering. There’s a persistent belief that Syria’s refugees will soon outnumber Lebanese people, fueled by claims that more than 2.5 million refugees reside in Syria. Some pundits even say that because some refugees have had military training, Syrians in Lebanon pose a risk and could at any time take up arms against the small country. (In government-held Syria, men are automatically drafted into the army, while some have also served in opposition militias.)

This, in addition to a slew of other mis/disinformation, has made many Lebanese fearful that the high number of Syrian refugees could pose a threat to Lebanon. They’re often talked about in terms of “civilian occupation” and “demographic change.”

The negative associations still left from the Syrian government’s role in Lebanon’s civil war have also combined with classist generalizations that refugees are dirty, uneducated, and criminal. These depictions are almost commonly accepted as fact.

Disinformation like “Syrian refugees are killing dogs and selling their meat to Lebanese” spreads like wildfire. Meanwhile almost everything is blamed on Syrian refugees—from the trash in the streets (Lebanon had a trash crisis that predates the arrival of Syrian refugees) to the street traffic (Lebanon’s urban infrastructure is infamously dysfunctional).

All of this often translates into violence against Syrians.

In one of the latest episodes of violence, in mid-May two Syrians—visitors, not refugees—were walking in a Beirut street when they were severely beaten by a group of men, causing one to be hospitalized. Last month, a Lebanese man was beaten and stabbed when he was mistaken for being Syrian. Last year, a group of mostly Syrian laborers, some of them children, were beaten and tortured by a Lebanese landowner.

The examples are unfortunately numerous.

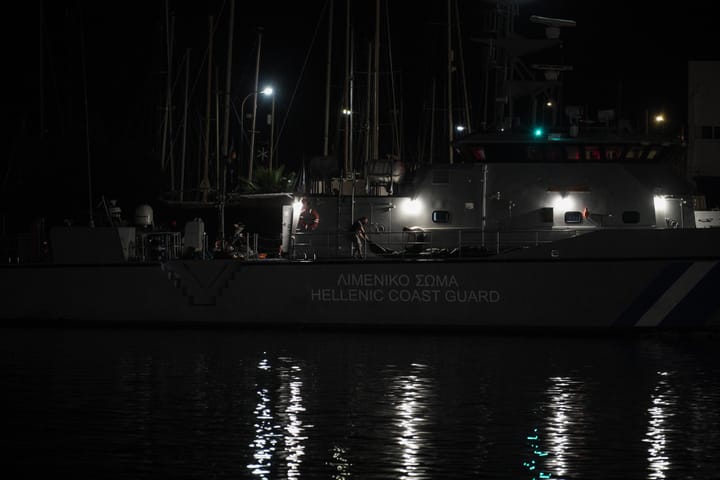

PS: Last October, you reported on a boat carrying Syrian, Lebanese, and Palestinian passengers that had set out from Lebanon with the hopes of reaching Italy. That’s an incredibly long journey, one that passes both Cyprus and Greece altogether. Their boat ran out of fuel, and more than a hundred people died. Are these kinds of dangerous migrations increasing now? And should we expect to see more of these “death boats,” as some referred to them in your piece, in the future?

NH: The vast majority of people who try the deadly sea crossing are Syrians, although they have increasingly been joined by Lebanese over the last few years.

And with UN-facilitated refugee resettlement a slow and arduous process, many refugees would prefer to risk their lives with the dangerous sea crossing rather than risking further hostility, humiliation, or deportation.

As the economic situation gets increasingly desperate here, I don’t see these attempts stopping anytime soon.

In 2022, UNHCR said the number of people attempting the dangerous Mediterranean crossing had more than doubled for the second year in a row. Earlier this month Frontex, the E.U.’s external border agency, said migrant crossings via the Mediterranean Sea had reached unprecedented levels in just the first four months of 2023. If the last two years are any indication, we can expect the number of people to depart Lebanon by sea crossing to increase. It’s not just Syrian refugees, either. Palestinian refugees, who face systemic discrimination and are legally excluded from working in most of the formal labor market, are also leaving.

Finally, there’s been a notable increase in Lebanese nationals attempting the crossing. As Lebanon’s economic situation continues to deteriorate, with more than 80 percent of the population impoverished, we can expect to see more of that. They all agree on one thing: they’ll risk their lives for a chance at a better one.

PS: You're Palestinian and Syrian, and you report often on the struggles of both of those populations in Lebanon. Is it a challenge to report on issues that hit so close to home?

NH: It’s uncomfortable for me to talk about because I love Lebanon and its people, so I never want to give people the wrong idea. There are sometimes challenges to reporting here, especially lately with the recent anti-refugee escalation. There is a marked difference in how my foreign western colleagues are treated while conducting interviews, compared to the occasional hostility I get as a Syrian, albeit American, correspondent.

I mostly report on Lebanon’s affairs. In some situations, I’ve faced aggression, discrimination, or people refusing to be interviewed by me after hearing my accent. But all that is par for the course for journalists—we’re all bound to face hostility at one point or another in our career, depending on the situation. You learn to brush comments off and push forward with the interview.

Most of the people I speak to are kind, intelligent people who have simply fallen prey to misinformation campaigns, or who have been traumatized and shaped by Lebanon’s complicated and violent history. I don’t hold it against anyone. It’s my job as a journalist to understand Lebanon. “The good, the bad, and the ugly," as they say.