In-conversation: Reece Jones on the U.S. Border Patrol's History of Impunity

Author and academic Reece Jones discusses the U.S. anti-migrant movement and deadly borders around the world.

Author and political geographer Reece Jones’ latest book, Nobody Is Protected: How the Border Patrol Became the Most Dangerous Police Force in the United States, opens on a traffic stop one evening in March 1973. In that incident, a pair of Border Patrol agents chased and eventually pulled over a car cruising along Interstate 5, not far from San Clemente, California, about sixty-six miles up the coastline from San Ysidro Port of Entry between the U.S. and Mexico.

The agents’ suspicion that the driver, Felix Brignoni-Ponce, was a Mexican citizen proved inaccurate, but they found that the two passengers didn’t have documents that authorized them to be in the country. The agents handcuffed and arrested all three, but the charges against the passengers, a Guatemalan woman and a Mexican man, were dropped after they testified against Brignoni-Ponce, who’d been charged with knowingly transporting illegal aliens.

With time, the case climbed its way up the legal system on appeals until it reached the U.S. Supreme Court two years later. There, the justices had to decide whether Border Patrol’s reach allowed it to violate the Fourth Amendment by effectively allowing unreasonable searches and seizures. The court ruled against Brignoni-Ponce in a decision that, as Jones writes, “continues to shape the lives of hundreds of millions of American immigrants through the present day.”

It’s a scenario that repeats several times throughout Nobody Is Protected, a deep dissection of the history that led the Border Patrol to become one of the most feared and well-funded law enforcement agencies in the country.

We spoke with Jones, a professor at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa and author of seven books, about the U.S.’s ever-expanding borderlands, the Border Patrol’s unchecked authority, and where, if anywhere, one is protected.

Long Road Magazine: In Nobody Is Protected, you dive deep into the U.S. Supreme Court’s role in shaping what’s hard to view as anything other than the immensely outsized authority the Border Patrol commands in the country. But before you take readers into the halls of the nation’s top court, you take a hard look at the violence carried out by predecessors like the Texas Rangers. How does that history continue to influence Border Patrol today?

Reece Jones: Although most people assume the United States has always had a Border Patrol, it was not established until 1924, two days after the passage of the Johnson-Reed Immigration Act. That law was steeped in eugenics and created strict limits on immigration from everywhere except Northern Europe and the Americas. The New York Times front page headline on April 27, 1924, was “America of the Melting Pot Comes to an End.” The article said the “chief aim” of the law was “to preserve racial type as it exists here today.” So, the Border Patrol was created as a racial police force to prevent the immigration of nonwhite people to the country. The first agents were hired directly from frontier law enforcement like the Texas Rangers, who had Wild West notions of the use of force and experience with the displacement and extermination of Native Americans. That is the origin of the Border Patrol.

LRM: After a Minneapolis police officer killed George Floyd in late May 2020 and ignited protests the nation over, many expressed shock at Border Patrol’s presence in cities that had become flash points for protests against police brutality. That July, Border Patrol started snatching people off the street in Portland, hundreds of miles from the Canadian border and more than a thousand from the U.S.-Mexico border. How and why were Border Patrol agents policing protests in a place like that?

RJ: In Nobody is Protected, I show that the Border Patrol was originally meant to operate only at the border line itself, not in the interior of the country. In the early years, the agents ignored that directive and eventually, in 1946, Congress revised the Border Patrol’s authorization to say they could operate inside the U.S. but “within a reasonable distance” of the border. In 1947, in an administrative decision taken without public comment or debate, that distance was set as 100 miles of borders and coastlines. That distance has not been reconsidered since, which means the Border Patrol has special exceptions to Fourth Amendment protections against unreasonable searches and seizures in a vast area that includes the homes of almost two-thirds of the U.S. population, and most of the largest cities, such as Boston, Chicago, Los Angeles, New York, and Washington, D.C.

Although Portland is inside the 100-mile border zone, the Border Patrol agents that were grabbing people off the street in unmarked minivans in the middle of the night were operating under a different authorization, section 40 USC § 1315. This is a post-September 11 provision that the Trump administration invoked during the Black Lives Matter protests in the summer of 2020 that allowed the secretary of the Department Homeland Security to reassign federal agents to protect government property. The designated agents can make arrests without a warrant for “any felony cognizable under the laws of the United States” and can “conduct investigations, on and off the property in question.” The provisions are broad and with an expansive interpretation could be seen as authorizing a national police force in the U.S. Despite Democratic control of Congress for the past two years, these provisions were not revised, which means they remain in place for a future authoritarian president to use, if they wish.

LRM: In recent years, especially during Donald Trump’s presidency, anti-migrant politicians openly ratcheted up with worrisome frequency warlike rhetoric. Trump’s campaign regularly described people crossing the border as an “invasion,” language that echoed what has emerged in white nationalist manifestos like the one penned by the gunman who shot and killed twenty-three people in an El Paso Walmart in August 2019. Later still, that language became standard fare during this year’s midterm elections. Texas Governor Greg Abbott has ramped up fears of a supposed invasion. In Arizona, the Kari Lake failed gubernatorial candidate spoke of an “invasion.” In rightwing media outlets like Fox News, it appears to have become part of the style guide. But in your book, you cite newspaper reports from The New York Times and others that used similar language decades ago. How baked into the discourse is this kind of rhetoric, and does it pose danger to society at large?

RJ: My previous book, White Borders, documented the connections between U.S. immigration laws and white supremacy. I decided to write that book in order to understand whether Donald Trump’s racist and nationalist rhetoric around immigration was a new development, or if it fit within the longer trend in the country. What I found was that the language today that depicts immigrants as violent invaders who bring crime, drugs, and disease to the country is a carbon copy of the way immigrants from China were described in the late nineteenth century. In each era, restrictions on nonwhite immigrants were justified based on the claim that without them the white population of the country would be replaced. I make the connections between earlier ideas like “the passing of the great race” or “race suicide” and today’s rhetoric around “white genocide” and the “great replacement.” What is particularly concerning is that when I started writing the book, mainstream rightwing figures were still reticent to use Great Replacement language. By 2020, the idea was espoused by Republican leaders in Congress like Elise Stefanik and commentators like Tucker Carlson on Fox.

LRM: In your 2016 book, Violent Borders: Refugees and the Right to Move, you interrogate the massive security apparatuses built to police international boundaries. You also unravel the tragic paradox of ballooning “border security,” which, in many places, has only made borders deadlier places. You take readers to the European Union’s external borders, the India-Bangladesh border, and the Israeli wall in the occupied Palestinian territory. What, if anything, makes the U.S.-Mexico border unique when compared with places like these around the world?

RJ: I don’t think the U.S.-Mexico border is unique. Violent Borders demonstrates the global trend toward hardened borders to protect economic and cultural privileges. You can see this trend in the dramatic increase in migrant deaths and in the emergence of an enormous border security market for corporations to sell their military and surveillance products. The increase in the number of border walls around the world illustrates the growth. As late as the year 2000, there were only about fifteen border walls globally. When my book Border Walls came out in 2012, there were thirty-five [border walls]. Today there are over seventy, with more planned every year.

LRM: In 2022, it was reported that the last fiscal year marked the deadliest on record for those making the journey across the U.S.-Mexico border. According to government data, more than eight-hundred people had died. Many have pointed out that the tally is almost certainly an undercount. Still, what accounts for the growing number of deaths on the southern border, and do you expect that number will continue to rise?

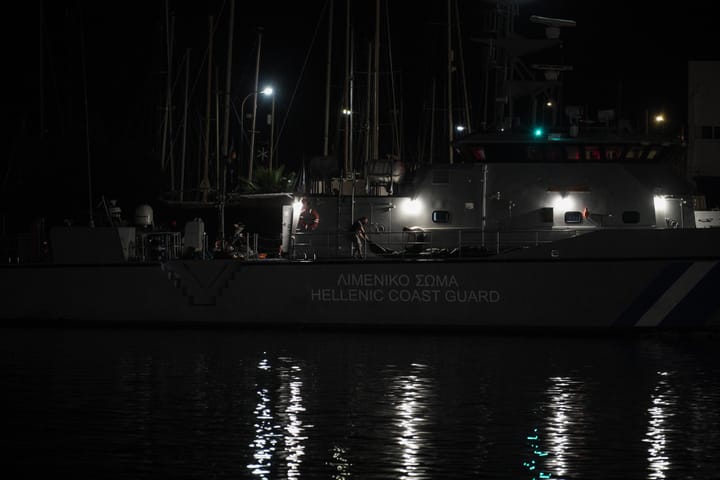

RJ: Sadly, the increase in deaths at the U.S.-Mexico border is matched by an increase in deaths globally over the past twenty years. The cause is clear. As countries fortified borders around the world, it has not discouraged people from attempting to migrate, but it has made the journey much more dangerous as they are forced into ever more remote locations. Whether it’s dangerous sea journeys across the Mediterranean, from West Africa to the Canary Islands, or from Haiti to Florida, or seventy-mile treks through the deserts of the Sahara or Arizona, people on the move face ever-more risky routes to seek safety. With the risk of displacement from climate change on the rise, the coming decades portend even more deaths at borders globally.

As a final thought, I want to remind everyone that it does not have to be this way. Humans have migrated for millennia and will continue to do so in the future. Those who find themselves in safe and privileged locations have a choice. One option, which most countries have taken so far, is to invest heavily in violent borders by building more walls and hiring more guards to prevent the movement of other human beings. The other option is to invest in safe journeys and welcome facilities for people on the move when they arrive. Rather than walls and weapons, that money could instead be spent on social workers, language instructors, and job trainers. Rather than violent borders, we could have vibrant borders that facilitate the movement of people around the world to the benefit of countries on both ends of the exchange.