In-conversation: Stefania D’Ignoti on Migration and Sex Trafficking in Italy

Stefania D'Ignoti discusses her recent longform piece on migration and sex trafficking in Sicily.

Deceptions, curses, and a perilous voyage—each year, tens of thousands of Nigerian women are trafficked to Sicily after being promised jobs and a shot at a better life. But in Italy, most wind up in the clutches of criminal organizations that force them into sex work.

In her recent feature at Long Road Magazine, Stefania D’Ignoti explores the risks Nigerian women endure along the way to Europe, the dangers they face once they are in Sicily, and the work of one woman who helps them escape.

D’Ignoti is a freelance journalist covering Italy and the broader Mediterranean. Focused on migration, conflict, women’s rights, and organized crime, her work has appeared in National Geographic, Foreign Policy, and The New Humanitarian, among others.

A graduate of the Columbia Journalism School, D’Ignoti is the winner of the Maria Grazia Cutuli International Journalism Prize and the Migration Media Award. Most recently, she received the Kim Wall Memorial Fund reporting grant through the International Women’s Media Foundation for her piece, “Finding Shelter.”

Long Road Magazine: Stefania, can you start by telling us a little bit about the reporting you’ve been doing over the last several years, and how you ended up coming across this story?

Stefánia D’Ignoti: Well, first of all, thank you so much for inviting me. So, I’ve been covering migration and refugee stories for the past five years, more or less, as a freelancer and my region of specialty is the Mediterranean area, so mostly Southern Europe and the Middle East. And since I’m originally from Sicily I’ve been covering a lot of these kinds of stories from my homeland. Since I’m from there, that’s how I found out about the story of Nigerian trafficking, and it’s a story I’m familiar with since I was in high school or undergraduate university years. But when I became a journalist, I wanted to tackle it from that perspective. And I totally think that my origins are what pushed me to become the person I am today and to cover this topic as a journalist: coming from Sicily and being exposed to migration since a very early age. We tend to associate the refugee crisis with the year 2015, but in Sicily this has been happening since the 1970s and 80s, so even before I was born. I grew up in this environment that really exposes locals to migration, and Sicily is a crossroad in the middle of the Mediterranean that hosts a lot of people coming from North Africa or sub-Saharan Africa. They just land here sometimes and then move forward to Northern Europe, where some of them stay. So, my lived experience as a local here in Sicily really inspired me to write the stories that I’m covering today as a journalist.

LRM: You received the Kim Wall Memorial Fund grant to pursue this underreported story. Can you tell us a little bit about why you chose this story? Was there a central character that made you immediately think this story needed to be told?

SD: I was lucky enough to receive financial support for this story. I thought this story really needed a deep dive into the reporting—the kind of slow journalism that freelancers often don’t have the time to dedicate to because they don’t have the financial resources for it. So, I thought applying for a grant would give me the chance to give a better idea of the story and to just give me the time it needed to be reported. The scope of the Kim Wall Memorial Fund really resonated with this kind of story because Kim wanted to cover underreported stories that often had strong female characters, so I thought this story really fits—it’s a nice match with the scope of this grant. I thought the central character, which is Egbon, really made a great character for this piece because she’s a strong female lead who created something that never existed before in Sicily, and as far as I know not anywhere else. She’s a strong Black woman in Europe, who was trafficked and still managed to save herself and is also now trying to save others in the same condition without waiting for outside help from institutions or Italians. That’s why I thought this kind of underreported story was really, it really fit with the scope of the grant.

When journalists portray migrants, they often portray them as victims. But this story actually shows that they can take their own destiny in their hands; it doesn’t show them as victims but rather as active agents of their own future in Europe—instead of always being the ones asking for help from outside institutions.

LRM: You mention in the piece that the survivors often find it hard to trust Italian organizations and volunteers, but what about journalists? Was it difficult to gain the trust of the women you spoke to?

SD: It was definitely difficult. I was coming to the community as an outsider, and I’m also not a minority journalism myself. I felt that when I was trying to gain their trust there was some suspicion from their side. But the fact the [Egbon] Osas was always with me kind of helped me gain their trust. I think that if I hadn’t known Osas and I hadn’t spoken to her extensively first, this article probably would not have had the same impact and the same depth, because it’s really hard to gain the trust of these women; we have to take into consideration the fact that they’ve been trafficked, they’re often traumatized, they’re very suspicious towards Italians because they just live often in this bubble where they’re controlled by the Nigerian mafia and they hardly come into contact with Italians other than as their clients. So, it’s really hard, and it was really hard for me to gain their trust at first, but if you have an insider like Osas who helps you connect with the rest of the sources, then it’s more manageable.

The fact that they don’t really trust Italian journalists in particular because even if this is a topic that’s not super new—it’s underreported, but there have been foreign reports about Nigerian trafficking to Italy—and the fact that it’s mostly foreign journalists who cover this story, and almost never Italians, that also kind of created that extra element of distance between me and them. I thought that was also an interesting point—that for them it’s so unusual to have an Italian journalist covering this story. Also, they wanted to know a bit more about me and about my previous reporting—so the fact that I showed them that it was not the first time that I was covering a story related to migration and trauma helped. Since they all spoke English they had a chance to see my previous work, so they knew the kind of journalism that I came there to do was not meant to hurt them. That’s also what made them trust me, I think. And it also helped that I am a woman—so, even though I was a foreigner and am not a minority journalist, it also helped somehow that I was a woman.

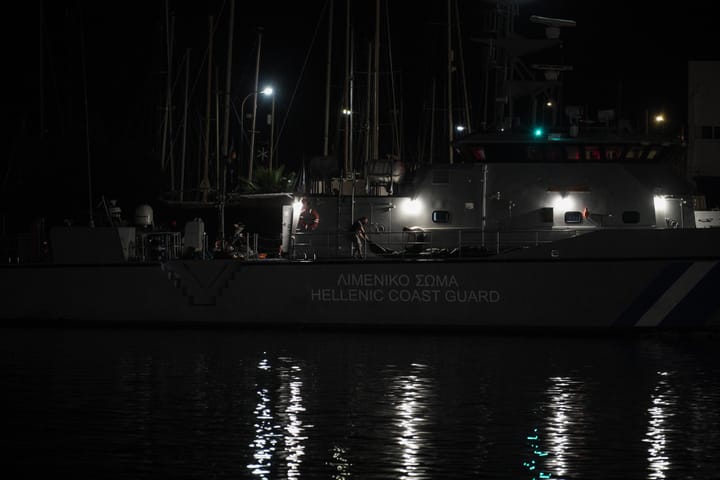

LRM: The journey across the Mediterranean has never been a safe one, but it’s becoming increasingly more dangerous given the growing anti-migrant sentiment and actions like we’ve seen in November of last year when Italy’s new government refused to let 900 migrants disembark in the Sicilian port of Catania. What does the situation look like going forward?

SD: The situation is slowly getting worse. We had an example of that in early January. The new right-wing government published a decree that put some limits on sea rescues. One of the examples is that it’s the obligation from the captain of the rescue vessel to ask for permission to head towards an Italian port, and if that’s not respected and the vessel goes directly to the port without having been granted the permission to disembark, the NGO might get fined between 10,000 and 50,000 euros and even have their vessel confiscated. All these measures are being taken to discourage NGOs from working in the search-and-rescue area in the Mediterranean, and specifically to discourage disembarking at Italian ports. Going forward, it is unfortunately not looking brighter—since a new right-wing government has come to power in Italy, the stance on migration is only going to get harsher by the day.

LRM: How do these hardline policies make the situation for Nigerian women who have been trafficked to Italy for sex work even more difficult?

SD: In 2018, the then minister of interior published a decree that basically stripped asylum seekers of their right to ask for asylum if they were not directly coming from conflict zones. That mainly affected women like Nigerian trafficked women. Because Nigeria is currently not a war-torn country, they wouldn’t qualify to apply for asylum or humanitarian protection. That stripped them of many rights. Many of them want to get out of this trafficking circle, but they can only do so if they know that they have some institutional protection. The few people who tried to apply for humanitarian protection before the 2018 law [came into effect], they basically saw their rights blocked for a few years, until the decree was lifted again. It basically upended their lives, because they’re already in a difficult situation, many of them are scared to get out of that life and then not being legally protected anymore had a huge impact, because this also collided with the fact that back in Nigeria the priests cursed the traffickers of doing something against their own religion. This really changed the situation for them, and still today this anti-migrant sentiment and this new decree that just came out will also affect them. Many of them don’t come by plane anymore, like it was during the ‘80s—they take the cheaper routes, like the sea route from Libya—so, many of them come by boat. The fact that they’re not allowed to apply for asylum while they’re on the boats or that they will not have much legal protection once they disembark and they arrive in Sicily, it has a huge impact on their lives going forward.

LRM: Does it sometimes feel like the system punishes these trafficked women as much as or even more than their traffickers? Have there been many cases of traffickers or madams being apprehended and punished?

SD: One interesting thing to notice is that it’s not only the trafficked girls who often come by boat, but some of the traffickers themselves also come. The Nigerian mafia is the second biggest mafia in Italy—it’s called the Black Axe—and many of them were coming by boat. In the past few years, Sicilian authorities have realized that even in reception centers, there were some members of this Nigerian mafia. They targeted them from a legal perspective, but not for trafficking; rather for drug dealing, which was easier to testify to instead of trafficked women. That’s because many of the women were scared to accuse them. The easiest way to block them, from a legal perspective, was accusing them of drug dealing because that was something that was easier to prove. I remember in the last year there has been around a dozen custody orders from Sicilian courts against some of the Black Axe members, but these processes don’t actually go anywhere. It’s in the initial stage, but then they just don’t go any further. Even in cases where there has been murders of these girls—I remember in 2011 and 2012, there were two cases of murdered Nigerian girls in Palermo, and no one was ever found guilty of those murders. It’s just the system that already has too many problems to deal with, so this trafficking topic often takes a backseat. It doesn’t really go [as far as] punishing the traffickers.

LRM: That brings up the issue of justice. If some traffickers are being apprehended but then only tried for drug dealing, there still is no justice for these women who would like to see them punished for the specific crimes that were committed against these women.

SD: It’s often the women themselves who must pay the biggest price. Even to get out of that life, they have to pay a huge amount of money. They pay a big price both in financial terms and in moral terms. That’s also what Osas is trying to change, like also to create a safe space where feelings of shame or guilt can just crumble down. I think it’s really hard to find these kinds of safe places that let women live a long-term life without guilt and without shame, but it’s an example that really gives hope—the fact that there’s a place like this so it gives hope to women who want to get out that kind of life.

LRM: You mention a safe place that these women need and that it’s not only physically feeling safe, but it’s also the emotional and the psychological element of feeling safe. But I do wonder about the women who do manage to escape the clutches of their traffickers. Do their traffickers and madams or someone involved in that circle come looking for these? Do they have to go into hiding? Is this why, or one of the reasons why, Egbon’s safe house is hidden away as well?

SD: As far as I’ve understood, most of the time they manage to come to an agreement with their traffickers. They pay a huge amount of debt, but they still negotiate that freedom. So once they get out and they have the financial stability to support themselves, and also the emotional support of people like [Egbon] Osas, then they can move forward without having too many issues with their traffickers. Even though they will still try to lure them back into that ring, it’s not like they chase them or anything. But, in very few cases they just run away without paying the debt so that’s why it’s safer for Osas to have this place in the middle of nowhere so it’s safer for them to hide in case there are any problems—if their previous traffickers find them or see them in the streets of Palermo, [for example]. So, I think it’s a combination of the two.

LRM: Is there hope for a brighter future for these women?

SD: I think there is [a brighter future in] the kind of hope that they can see in people like Osas and in places like she’s trying to create. It’s really hard for them to trust Italians, as I’ve said, and there have been some NGOs working in Italy to try to give them a safer alternative than the life they’ve been condemned to when they come to Europe. But I think the only hope is that more formerly trafficked women set an example for the current girls so that they can free themselves and they can actually lead a normal life in Europe without having to be forced into sex work. I think in terms of policies it might be hard to think of a bright future for the moment but definitely from the grass roots level people like Osas are really those who are managing the change.