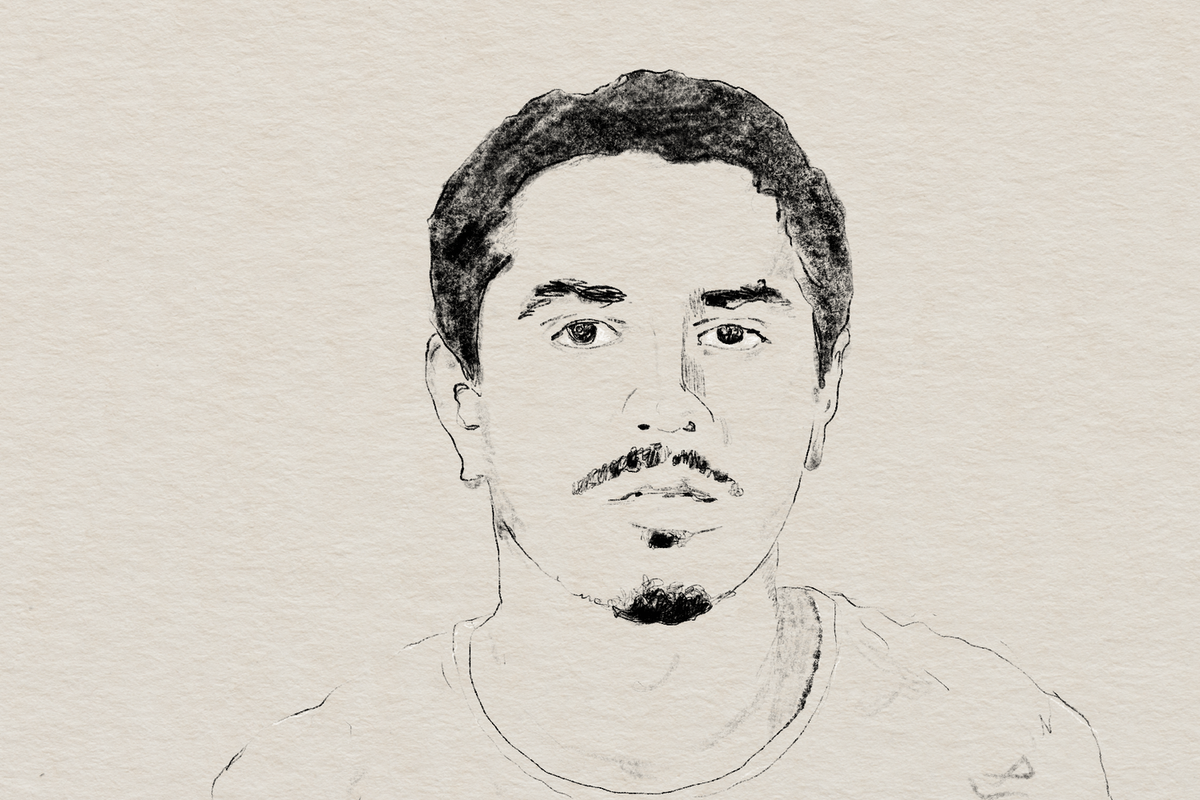

In-conversation: Victoras Antonopoulos on Refugees and Turkey's Deadly Earthquake

Victoras Antonopoulos discusses his recent reporting in earthquake-ravaged southeastern Turkey.

When Victoras Antonopoulos and his colleagues traveled to southeastern Turkey in February, an earthquake had just turned much of the region into piles of rubble. Tens of thousands died on both sides of the Turkish-Syrian border, and homes and other buildings were reduced to mounds of busted-up concrete and mangled steel.

Antonopoulos, a journalist from Athens, Greece, had hoped to speak with locals as well as Syrian refugees who now faced displacement yet again. But during his reporting, speaking with Syrians proved a difficult task.

At one refugee camp, the manager forbade him from speaking with anyone at all but allowed him to take photos. Elsewhere, some told him most refugees feared talking to the press—the Turkish government, they said, might retaliate.

His work and that of his colleagues came to a halt when Turkish authorities confiscated their cameras and phones. When authorities later smashed the cameras and phones, Antonopoulos lost many the interviews he had conducted throughout the trip. He recounted the trip and this experience for Long Road Magazine in a recent piece titled, “After the earthquake.”

Long Road editor Fahrinisa Campana recently interviewed Antonopoulos about that piece, the challenges he faced while reporting, and Turkish authorities’ decision to confiscate equipment belonging to him and his colleagues.

Long Road Magazine: Can you first talk a little bit about the work you’ve been doing lately and how or why you decided to cover the recent earthquake along the Turkey-Syria border?

Victoras Antonopoulos:

Actually, I’ve been a reporter for the past five years. I used to work in a radio station covering mostly breaking news or demonstrations, wildfires, things like that. There was a time last year when I thought that I don’t want to do only [that kind of work], I mean reporting from the demonstrations and stuff that I like, but I wanted something more. So, I decided to go to Moldova to report about the refugee crisis due to the Ukrainian war. So, I started thinking about doing feature stories and working as a freelancer. I quit my job in August and right now I still work as a freelancer, and after the earthquake I decided to go to Turkey to do [this], to write stories and take pictures, because I like this work—except for the breaking news part. I wanted to write about the [earthquake’s] aftermath and the consequences of something so big and so devastating.

I think people want to share their stories, that people affected by every crisis—whether it’s an earthquake or a refugee crisis. They expect journalists to help share their stories and to do so with dignity and respect for their points of view. I think it’s very important for us, as journalists, to understand that people want to be heard.

LRM: You and a handful of your colleagues traveled to southeast Turkey after the earthquake in early February. Tens of thousands of people died, with casualties on both sides of the Turkish-Syrian border. Can you give us a sense of what you saw and heard while reporting in the area?

VA: Because I went to Turkey a week after the earthquake, I didn’t see any rescues taking place. You see everywhere ruins and damaged buildings and people getting their things from their homes to leave. Basically, we saw a lot of people who were anxious and nervous, and of course, there were tent cities where people [displaced] by the earthquake were living. I saw cities that need to be rebuilt from zero. No one can live in these cities. They can only live in tents. But for how long?

For the most part, Syrians lived in the closed tent cities. In other cities, like Hatay, Turkish people lived [in tent camps]. As I wrote in the article, a Syrian man told me Syrian people aren’t allowed to live in specific tent [encampments], but I couldn’t confirm that. Still, there was a sense that the authorities considered Syrians enemies. For example, a [Turkish] soldier told me that he was there to protect me from Syrians who would steal my belongings, etcetera, etcetera.

LRM: Southeastern Turkey is home to a large population of Syrian refugees. In fact, the country hosts around four million Syrians. What was this earthquake like for those who’d already been displaced by war in Syria and were now living in the quake zone? In the piece, you speak a little about how local authorities tried to in fact hinder reporters’ ability to speak with Syrians? Can you explain a bit about what that experience was like?

VA: During some interviews, they told me that conditions in the tent camps were fine. They had food, for instance, but they were closed camps. Much like here in Greece, on Lesbos Island or Samos. [Authorities] didn’t want Syrians to share their stories, actually. They live in closed camps—I don’t know if they could leave these camps. I think they couldn’t leave, or only with permission. I couldn’t confirm this because no one will tell you the truth. But you leave your hometown and now you live in a tent city where no one can reach you. And journalists cannot interview you. So, how good can the living conditions be? I mean, it can’t be good for a person to live like it’s a quarantine. It was like a quarantine.

LRM: In your opinion, why were Turkish authorities so sensitive about media interviews with Syrians? In the end, you were able to speak to a few people, correct? What were their stories like?

VA: Yeah, we were able to speak Syrians in some open tent cities and people who lived in their own tents. But I think it differed based on the cities we were in. For example, when we were in Osmani, we couldn’t interview Syrian people, and we had the manager [of a refugee camp] following us to make sure that we wouldn’t do any interviews. But [we spoke to Syrians] in a village near Maras—it was a very small village, and they just didn’t have so many policemen and soldiers patrolling. I think it has to do with their inability to control so many people and so many damaged cities, that’s why we managed to interview some Syrians.

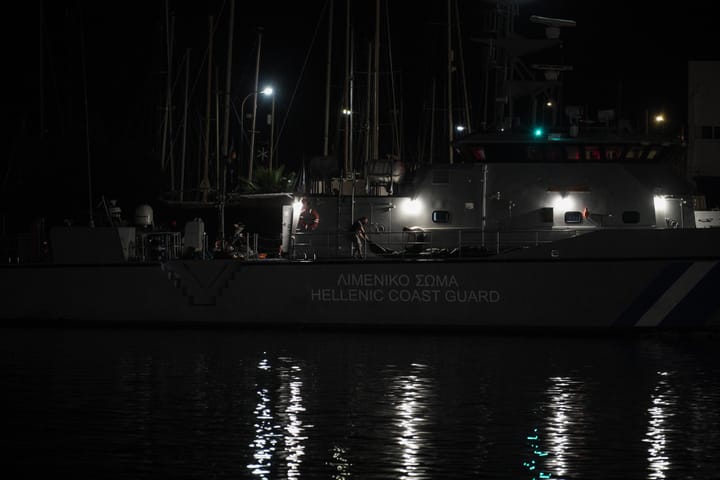

LRM: You also mention that some of those Syrians would now move on toward Europe. You’re based in Greece, where you’ve reported on the government’s migration policies before. What kind of treatment could Syrians or Turks now displaced by the earthquake expect on Europe’s borders?

VA: I think they don’t expect to live in tents. I’m sure they expect better conditions. I mean, living in a house is the basic condition a person can expect from a country. Also, they want to immigrate regularly. They don’t want to travel—I will say illegally, but I mean that many people cannot have the papers that the governments are asking for, because the terms are very difficult to be fulfilled so many people decide to immigrate through water and we see the aftermath of this, it’s devastating. So they want to do this legally in order to be safe. They know that if they decide to travel illegally, the authorities will chase them and maybe they will end up in a boat in the Greek islands. They do know this situation, I’m sure of it. For example, they want to travel to Athens, to live in a house and have papers, and maybe after that go to another country.

But they don’t want to experience the same thing they experienced when they left their homeland in Syria, where they had civil war. They don’t want to experience the same tragedy: I mean walking for thousands of kilometers to find a place where they feel safe.

LRM: You briefly allude to the fact that Turkish authorities confiscated your phone and broke it, along with your colleagues’ cameras. Can you explain how that happened and what that experience was like?

VA: We’d read in the news that mass graves have been created in some places, and we learned about such a place near Hatay. We read about it and saw videos and photos, and then decided to report there. We went by car, and they told us filming was prohibited. They actually said this to my colleague Kyriakos and me. They didn’t tell our third colleague, Konstantinos, who was ahead of us and had already started taking photos. He didn’t know it wasn’t allowed.

Kyriakos and I left that area. We went outside to the car to wait for Konstantinos. A soldier, a policeman, and a guy from a religious governmental organization ordered us to hand over our phone and Kyriakos’s camera. I didn’t give them my camera—I’d left it in the car. So, they took our phones and cameras, and of course, they did the same to Konstantinos. They told us they’d hold the equipment for three months. We contacted the Greek embassy, which told us that our equipment had been broken and we could go back and get it.

When I say the equipment was broken, I mean totally broken. They smashed the cameras, the sensors, the lenses. They stole the SD cards, the camera batteries. We’re talking about stealing. Even though they returned our stuff, some things were missing. I tried to recover files from my phone, but the hard drive might be broken. I cannot recover them. My sim cards were also missing—with my contacts and everything. They violated our privacy.

After this incident, we were very scared. We didn’t know what to expect until we left the country. We didn’t know what was allowed and what wasn’t. This all happened even though we had accreditation [as journalists].

For example, I asked a soldier if I could photograph in the area of Iskenderun. He told me I needed permission. I still don’t know what permission I needed to take photos in the street. I mean, I already had the accreditation card, so what other permission did I need? I decided not to take photos in that area. I was afraid I’d get arrested and they might take my equipment again. It was difficult to know what was allowed and what wasn’t.

And it wasn’t only us. We heard about other journalists that had the same experience. To be fair, it’s only in this one area where such things happened. It’s not in the whole region of southeastern Turkey. But okay, freedom of speech in Turkey is in a very low [standing]. I don’t want to say this incident was political. It seemed like the decision of some people running the place with the mass graves. They might have decided to do this to a journalist or photographer [beforehand].

In the rest of the region, I’ve read about some other experiences journalists had. I think it’s mostly about fear they’ve created for journalists. It was very difficult. I was lucky enough to save my camera. I think that’s why I managed to do any work at all from Turkey.